I first heard of Habibi Funk early last year but never delved in too deep. I didn’t even realise it was a fully-fledged record label. As far as I was concerned, it was some YouTube dude doing God’s work: finding really rare Arab gems from the 60s-80s and putting out mixes as good as gold.

But among my long list of assumptions, one was most crucial—I thought he was Arab. Turns out, Jannis Strütz—the man behind Habibi Funk—is German. Upon learning about his ‘non-Arabness’, my perception of his mixes slightly shifted, and suddenly my intrigue became tainted with a sense of confusion.

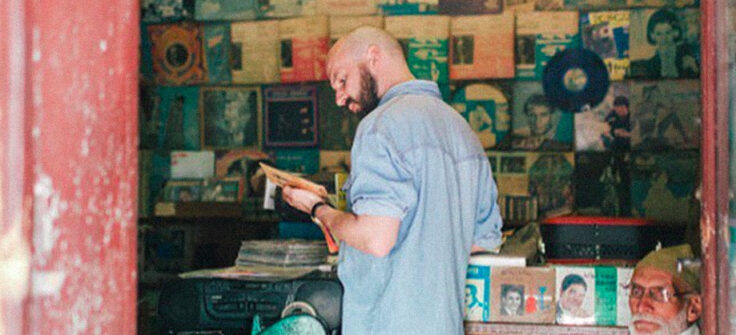

Strütz launched Habibi Funk in 2012 after a trip to Morocco where he came across an Arabic cover of James Brown’s ‘Papa’s Got a Brand-New Bag’. Since then, he’s become an archaeologist of sorts, digging up records at obscure record shops all across the region, from the Middle East to North Africa. He started by creating mixes and sometime later, decided to co-found a record label, reissuing the sounds he’d come across and liked.

Habibi Funk has released seven albums so far, and as time has passed the label has built quite the cult following. But I couldn’t help but wonder, just as many other Arabs probably have, how did Strütz become so enamoured with Arab music.

So when Strütz recently came and played in Tunis, MILLE decided to catch up with him and find out about how Habibi Funk came about, cultural appropriation, and whether or not he feels a certain responsibility towards the region.

What triggered the launch of your label? And why Arabic music?

A few years ago, I went to Morocco, and when I travel I always try to find records I really like. I was in Casablanca at a record shop looking for music. I found some stuff and after that I realized that a lot of people like the music as well. But there’s a huge disparity between the availability of the music on one hand, and the interest it could create. We wanted to bridge that gap, and make sure that music accessible and rereleased.

What was it like in the beginning?

First release was 2 and a half years ago. It took us some time to get started. Like the first album we released was by a guy named Fadoul, and it took us nearly a year to find his family. In the beginning we assumed he was alive, then found out he was dead. Eventually we found his family.

Are there differences in the way an audience in Morocco responds to the music and one Germany, for example?

I’m not sure I can pinpoint differences. But in general, we have the privilege of having quite a lot of good feedback and recognition for what we’re doing. I think there are a lot of labels that release music for western audiences, and I’m not entirely sure how we managed to be different from them.

I don’t think I can pin point that into one single thing either. But like Fadoul for example, he’s more known now in Morocco than he ever was during his lifetime. Young people picked up on him. He sung about drugs, depression drinking—the classic topics of the 1970s, so funny enough, the reaction you’re getting from people with these obscure releases is very often very similar whether it was someone in Berlin or in Casablanca.

You’ve become a bit of an archaeologist of Arabic music, but considering you’re European, how do you navigate running your label with the current conversation around cultural appropriation?

If you run a label that rereleases music from outside of the European world, it automatically puts you in a position of responsibility not to repeat historical patterns of economic exchange, of communication, of culture—and it starts with very trivial stuff, like we want to make sure our ideas are in order. We split the profits with the artists 50/50. We don’t own copyrights. We don’t need licenses for a certain number of years.

But it also includes the way we talk, the way we find a visual representation. We’re not going to have camels on our covers. And I mean, you have those covers in the region, but it’s something different if I do it, as opposed to when an Algerian artist decides that for himself.

Also, and I’m slacking a bit about this. We’re trying to make sure our covers are made in Arabic. We try to use Arabic in our social media communication—at least with the big stuff—and it’s not because I don’t think that the demographic that follows us in the Arab world don’t speak English. I think they do. It’s more a symbolic thing since we’re dealing with music that has Arabic lyrics—so I feel like that should be reflected in the way you hear about it.

You’re also pretty involved, even outside of the music, right?

Yeah, the whole aspect of contextualizing is also important. All of our booklets are pretty extensive, we interview the artist. We upload photos. Quite early, we started thinking about how we could contextualize the work outside of a direct musical release. We just had an exhibition in Dubai, and we’re working on another one in Algeria for early next year. I’m going to Sudan in August to work on a documentary about the jazz scene there. There’s a lot of projects around the music itself.

Is it difficult to find music in the region?

When I started doing mixes, which came before the label, I always had this idea, like maybe it’ll be tricky to find music but there’s always stuff. I always start thinking that something is pretty niche, and that certain sounds are very unique, and then I realized that there’s a ton of bands that make similar music. So, no as long as there are enough people still interested in the work, I don’t think I’ll run out of material.

What’s in store for you next?

The next thing I’m focusing right now is the Sudanese documentary. Basically, it’s about Sudan, and it’s about its vital jazz scene. I mean, they call it jazz, but the music is different to what the west defines as jazz. And when you meet all the old artists, they always tell you about the clubs there they used to play at in the 1970s. So, the idea is to take them back to those places and share their stories.

Photo courtesy of @habibifunk