“But Sarah, you’re not really Arab anyway”, is a sentence I often heard growing up in post-9/11 Paris and London. It made me realise just how much white people confidently associate Arabness almost exclusively with poverty, conservatism, backwardness or violence.

I would be lying if I denied the fact that I do have the “privilege” of being able to pass as Southern European (I’m often asked if I am Spanish or Italian), but funnily enough, this has never felt good. I’ve often felt even more ignored, discounted, and in some cases misunderstood, purely for that reason.

Born in Paris to a Tunisian father and a Syrian mother, I was raised in London, so my identity has obviously been very fluid. Some people could even say that aligning with a specific group is basically irrelevant.

But first and foremost, I am Arab. Both sides of my Tunisian and Syrian family came from partial Ottoman ancestry, but more than that, I am Arab because it is the identity I inherited from my Tunisian grandfather. He fought with the national movement (and was exiled), and then there was my Syrian grandfather, who was a patriotic diplomat. I am Arab because it is the history, the culture, the language and the rituals that I recognise myself in. I am Arab because this is how my family’s stories will live on.

Some might wonder why I would want to claim my Arab identity so fervently in 2019, at a time when the MENA region is ravaged and fragmented by wars and revolutions. A time when xenophobia against Arabs has essentially gone mainstream.

A few days ago I received a message on Instagram from a young Tunisian I had never met. It said: “You are not Arab, you are Tunisian”.

And this message upset me for a number of reasons. I shouldn’t be excluded from identifying as Arab just because I don’t have ancestors from the Arabian Peninsula. To accept this would be an acceptance of a monolithic definition of the Arab identity, one that was narrow. The very idea of being “Arab” has always been vast enough to include anyone who decides to embrace its unifying experience.

The Arabization of the region wasn’t even necessarily tied to Islam. In the 1860s, a reform known as the Nahda (‘rebirth’ in English) championed the redefinition of an Arab secular identity that was ethnically and religiously inclusive. Although it might sound surprising to some today, Baghdad for example, was 40 per cent Jewish until Israel’s inception.

I choose to identify myself as Arab because it is so diverse, and that is something I wish to celebrate; a definition of ‘Arabness’ that is intrinsically plural. One can feel Arab without giving up on or negating other things. There are light-skinned Arabs, dark-skinned Arabs, Berber Arabs, North African Arabs, Levantine Arabs, left-wing Arabs, right-wing Arabs, Muslim Arabs, Jewish Arabs, Christian Arabs, and also atheist Arabs. All are equal.

Hearing someone from my own background try to tell me that I am not Arab enough felt worse than when my white friends have done. It demonstrated how European colonialism has managed to manipulate the concept of identity so brazenly.

Through her words, I saw how colonialism has taught my people to fight against themselves by implementing “levels” of arabness between countries, and in other words, disapprove their own existence of a complicated yet very real and powerful identity.

To me, choosing to fully identify as Arab is a retaliation. It is not only political – it is revolutionary.

Life is a constant negotiation of ourselves. In our globalised world, we are all nuanced and each balance multiple identities. But self-acceptance of who I am reflects my staunch resistance to the divisions caused by colonialism and modern capitalism.

I choose to be Arab first and foremost because I decide to stand against the Western imperialist yoke, which has fragmented our nations to divide and conquer. I choose to be Arab because I wish to challenge populism and cast off those who punish us for being who we are.

In the words of author E. E. Cummings, “To be nobody-but-yourself — in a world which is doing its best, night and day, to make you everybody else — means to fight the hardest battle which any human being can fight; and never stop fighting.”

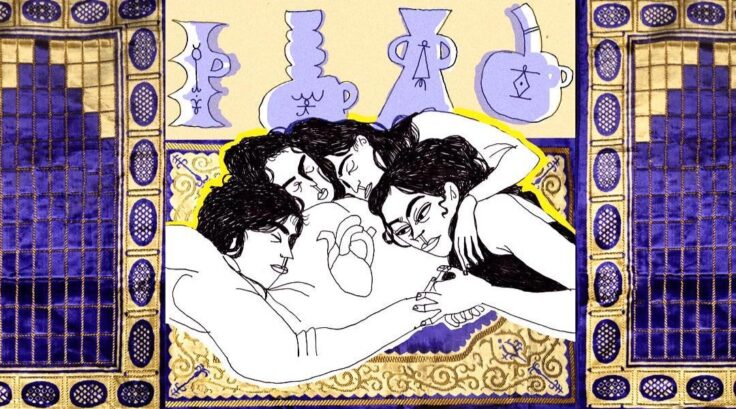

Illustration by @kahena.z