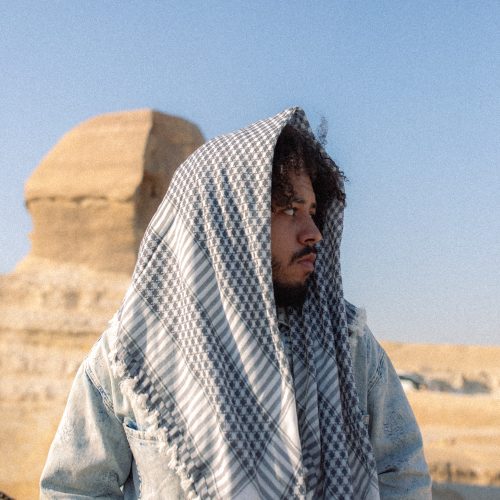

It’s summer 2019. It’s around midday on Chefchaouni street, one of Fez’s most popular and vibrant avenues. Elders swapped their stained work clothes for traditional djellabas for Friday afternoon’s sermon at the mosque. The neighbourhood’s youth gathered round the cafe, playing music as they sparked their Marlboro lights.

Brushing away the stress caused by lunch service, I drank my coffee in the back. I’ve also somehow become the DJ for the hour. By popular demand I was requested to play some Erkez, a renowned Tunisian band, but their name failed to appear on Spotify. They’re incredibly popular, though.

Of course, sarcastic laughter ensued, followed by sly comments mocking my use of Spotify. We were in a café after all, where all North African debates see their beginnings. Today’s? Why pay for a service that has numerous free alternatives?

Questions and doubts that music streaming platforms have timidly attempted to address through their launch in the region in vain were addressed on Chefchaouni street that day. Piracy is a common practice in the region, why would a 20-something young man pay to listen to music?

Launched in 2018, Spotify’s opening to the Middle East and North Africa was expected to help the Swedish giant reach new milestones. But the streaming platform’s introduction to this market has yet to fully prove its worth.

Very promising at first, their entry wasn’t without hurdles. As was the case for other streaming platforms, many obstacles have hindered Spotify’s journey towards revolutionising music consumption within the region. From projected glory to a realisation of a harsher reality, there are a few reasons why Spotify’s presence has not been rewarded with the expected acclaim.

At face value, the Arab world ticked all the right boxes for any streaming service to see success.

With a medium age of 23 and the number of smartphone users continuously increasing, the Middle East was naturally believed to be the next coherent market for music streaming services to take over.

There’s also the fact that there exists a whopping 285 million internet users across the region. This last decade has shown a lot of green lights to prompt a revolution in music consumption and to set up a more coherent and global institution that would promote, showcase and grant easy access to the many emerging talents the Arab world has to offer.

But high levels of connectivity, internet penetration and music consumption do not exactly entail the financial will or capacity to allocate money in streaming services. One thing—and perhaps the most important thing—to consider is the region’s poverty rates. According to the UN and with the $1.9 per day poverty line in consideration, the region’s headcount poverty ratio in 2015 averaged 5.6 percent—a statistic that has only increased since.

Considering the low disposable income available, the lack of financial means has been problematic for the pay-to-stream process to take place, only decreasing the benefits of investing and paying streaming platforms. Ultimately granting more resources and capital to the region’s artists and local talents, this is an educational process that Western music services have seemingly neglected so far.

Although such platforms’ freemium services cater relatively well, the Arab segment of the market is still weary of going premium as piracy and YouTube (well embedded habits and regional go-tos) only make it harder for Spotify and similar music streaming platforms to increase their presence and revenue. Pirated songs represent up to 95 percent of the shares of music consumption within the region and YouTube accounts for 47 percent of music streaming worldwide.

Piracy has rigged the region for decades which has only comforted YouTube’s position as main musical streaming resource. Even though Spotify was initially founded to fight piracy, their freemium service was arguably not convincing enough for Arabs, even after scaling their prices to local markets and currencies. Egyptian subscription fees are valued at 49.99EGP, which is substantially lower than other markets around the world for instance.

In a region dominated by cash payments, other competitors have tried to play their cards better. This was seen through Deezer’s initial investment in acquiring Rotana’s licenses to extend their catalogue, only making Spotify’s efforts look ever so shy and harder for them to compete with the aforementioned competitors as well as local actors such as the Lebanon-based Anghami.

Unlike their European counterparts, Anghami’s knowledge and footprint within the region remains unmatched to this day. After all, they understood one thing: the threat piracy poses to their company.

“It’s not like I’m afraid of competition from Spotify or Deezer or whatever,” Elie Habib, one of Anghami’s founders said in a 2019 interview. “I’m much more interested in competition with piracy and how we can actually help people or get people using a legal service.”

It can then be said that while Spotify or Deezer had a too general vision of the region through an understanding of its people as a homogenous monolithic group, Anghami has developed a much more acute sense of music in the Arab World.

Through better curated playlists, as well as a much more tailored experience on the platform, Anghami has taken the lead in a race that Spotify is far from being able to compete in. It turns out, the value lies within regional insight and awareness that remains unreachable with white-majority and non-Arabic speaking teams amongst many Western platforms’ Middle-Eastern divisions.

Regardless of whichever route Spotify decides to follow, all we can wish for is for local artists and involved actors to take advantage of the industry’s spontaneous ebullition, in hopes that it will only pave the way for a better and more sustainable scene to thrive on.