“A true piece of writing is a dangerous thing…It can change your life,” wrote US short story author Tobias Wolff in his 2003 book Old School. Indeed, writing can be a very dangerous profession. History records have lost count of how many writers have been jailed, tortured, and assassinated due to their authoring. A book is the oldest enemy of authorities, be it political or social. From throwing writers behind cells to organizing book burning rituals, societies and regimes throughout history have taken extreme lengths to keep supposed morals and ideas in check.

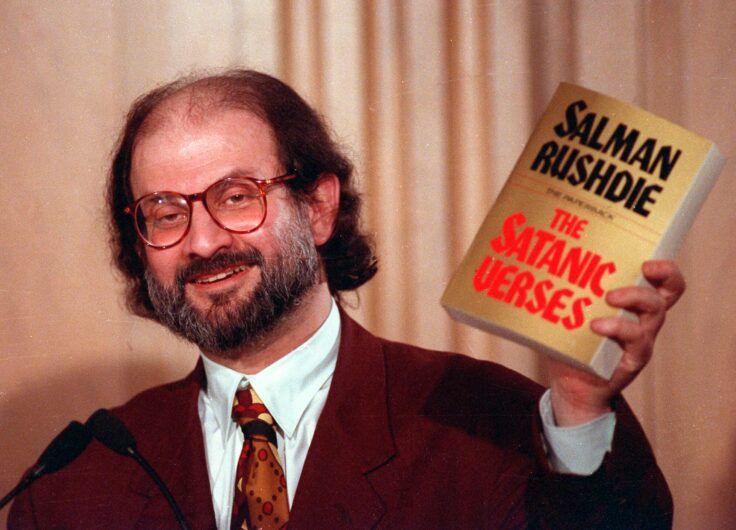

As a general rule, the majority of novelists don’t publish four books. And, if they do, they rarely cause widespread uproar and trigger assassination attempts. With The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie’s controversial 1988 book partially influenced by the Prophet Muhammad, the Indian-British author achieved both.

In addition to being burned in the UK, India, and Pakistan and banned in more than 12 countries, the “blasphemous” novel also prompted Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini to issue a fatwa, and a bounty of $3 million on his head. Violent threats related to the controversy amounted to his stabbing this Friday, August 12, 2022, as he was preparing to deliver a lecture in New York.

Rushdie was taken off a ventilator over the weekend, but he was still receiving treatment for wounds to his right eye, chest, and stomach, as well as a cut on his right leg and three stab wounds to his neck. He may also lose his right eye in the wake of the knife attack. In a statement to Sunday, his son Zafar Rushdie said: “Though his life changing injuries are severe, his usual feisty and defiant sense of humor remains intact.”

Since the fatwa, many of Rushdie’s collaborators were attacked and even killed in the same way. Hitoshi Igarashi, who translated The Satanic Verses to Japanese, was fatally stabbed in his office at the University of Tsukuba in 1991. The Turkish Aziz Nesin, the Norwegian William Nygaard, and the Italian Ettore Capriolo all survived similar fatal attacks.

While the history of banning books stretches back to the dawn of the written word, The Satanic Verses is deemed one of the most controversial cases, wavering for 25-years.

Not that long ago, a law prohibiting the import and distribution of books printed in Russia, Belarus, and temporarily occupied Russian territories was approved by the Ukrainian Parliament. Some western countries joined these measures, as an Italian university suspended courses on the great novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky as an act of solidarity.

Everywhere in the world, there is at least one banned book, and our region is no exception. From Naguib Mahfoud, who received death threats because of his books and Nawal Saadawi, who was jailed under former Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s regime to Ayat al-Qormezi, who was imprisoned and tortured after reading some of her poetry in a protest, citizens and authorities contributed in this impassioned fight against books.

Just like Rushdie who has continued writing despite all the threats, many brave souls have also challenged labels like blasphemous, obscene, and unpatriotic in the Middle East. In honor of their courage and freedom of expression, here is a list of controversial books written by writers from the Middle East.

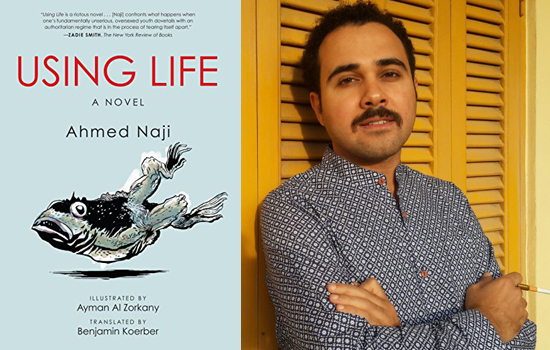

Ahmed Naji, ‘Using Life’

Ahmed Naji’s case is very unique as it is considered the first instance of Egyptian censorship in modern times based on public morals and family values. The novel was approved by the Egyptian censorship board before its publication. It all went well until a newspaper published an excerpt from the novel. An Egyptian citizen filed a complaint accusing Naji of violating public morals and the Egyptian family values and principle. The plaintiff reported to the court that he had heart palpitations and low blood pressure after reading the excerpt.

In 2015, Naji was sentenced to two years in prison and spent 10 months in jail before being released and obliged to pay a fine.

Using Life is a dystopian novel about Cairo before a natural destruction due to violent sandstorms and earthquakes. It revolves around Bassem Bahget, the protagonist, who is drawn in retrospection and nostalgia.

Saud Al Sanoussi, ‘Mama Hessa’s Mice’

One of the prominent Kuwaiti writers and an important name on the Arab literary scene, Saud Alsanoussi tackles many complex issues like racism, bedoun, and xenophobia in his book. The ban on his third novel took everyone by surprise as his second book was turned to a riveting social drama with the same title in Ramadan 2016.

Although he declared that he self-censors himself as “a preemptive measure,” he was not immune from governmental censorship. His book Mama Hessa’s Mice was banned from the Kuwait International Book Fair by the Ministry of Information respectively in 2016 and 2018.

Alsanoussi went to court to defend himself and lift the ban on his book. In 2018, he succeeded in annulling the ban and paved the way to loosening book censorship laws.

Mama Hessa’s Mice follows the story of Fuada’s Kids, a group of friends, who are striving to alert the country to the dangers of hatred, intolerance, and fundamentalism.

Mohamed Sghaier Ouled Ahmed, ‘Ilahi’ (My God)

Opposed under the regimes of Habib Bourguiba and then Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, the writer published his first book of poetry in 1984, which was banned and censored for four years. In 1993, he refused the National Order of Cultural Merit awarded by the deposed president.

After the Tunisian revolution, He received death threats and was assaulted and harassed by Islamists. Until his death in 2016, Ouled Ahmed was victim to violent attacks culminating in physical assaults, some of them in front of public institutions and under the eyes of policemen. A petition to remove him from the official poet board was published online by ultra-conservative groups.

In 2015, he explained his poetry has “been dictated by inordinate love for Tunisia,” at an evening organized in his honor by the Ministry of Culture and Heritage Preservation. “Tunisia is also my mother’s first name,” he added.

Through his words, Sghaïer Ouled Ahmed has become the spokesman of an oppressed generation, enamored of a wind of freedom, and a spirit of revolt.