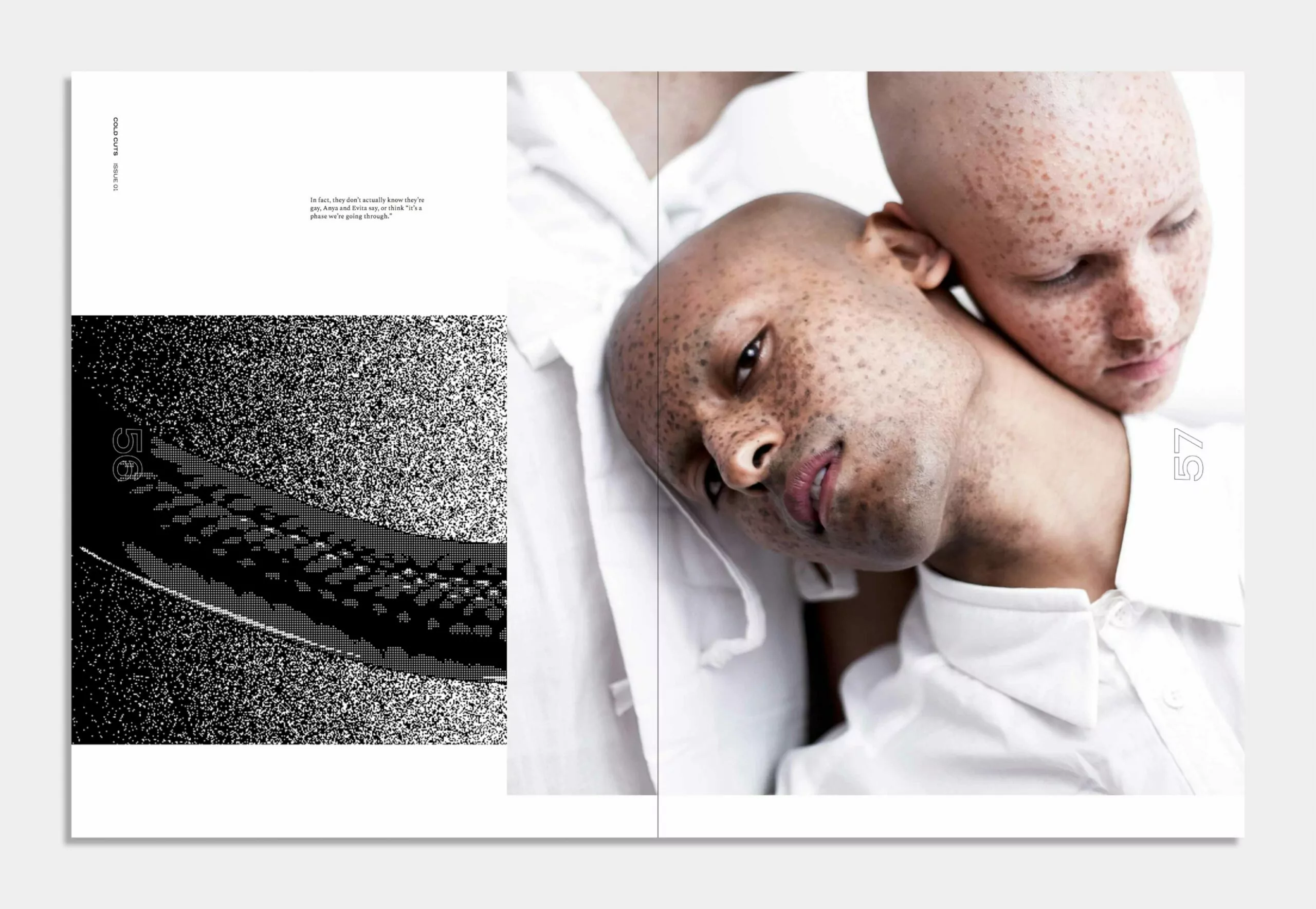

Representation is often overlooked. This statement might seem somewhat farfetched in the rest of the world, but when it comes to queer communities in the Arab world, nothing could be truer. And although it might be too late to tell the stories of the marginalised communities of the past, Mohamad Abdouni has made it his mission to provide a safe space for the present.

Together with art director Tala Safié, and fashion editor Charles Nicolas, Abdouni launched Cold Cuts Magazine in 2017. “It came about quite naturally,” he says, “It’s about my family, my very extended family and my community,” referring to the LGBTQI++ communities of the Arab world.

The magazine’s ethos? Documentation. “We’re working on transcribing the stories of people who are both still with us and not” he says. “We cannot rely on other people to tell our stories.” Having already released their first issue, where the Beirut-based publication impressively and truthfully documented the work and lives of queer Arabs from around the globe in 176 pages, in not one, but three languages (Arabic, English, and French).

We caught up with Abdouni to talk about his mission, and why we can’t rely on other people to tell our stories.

How did Cold Cuts magazine come about?

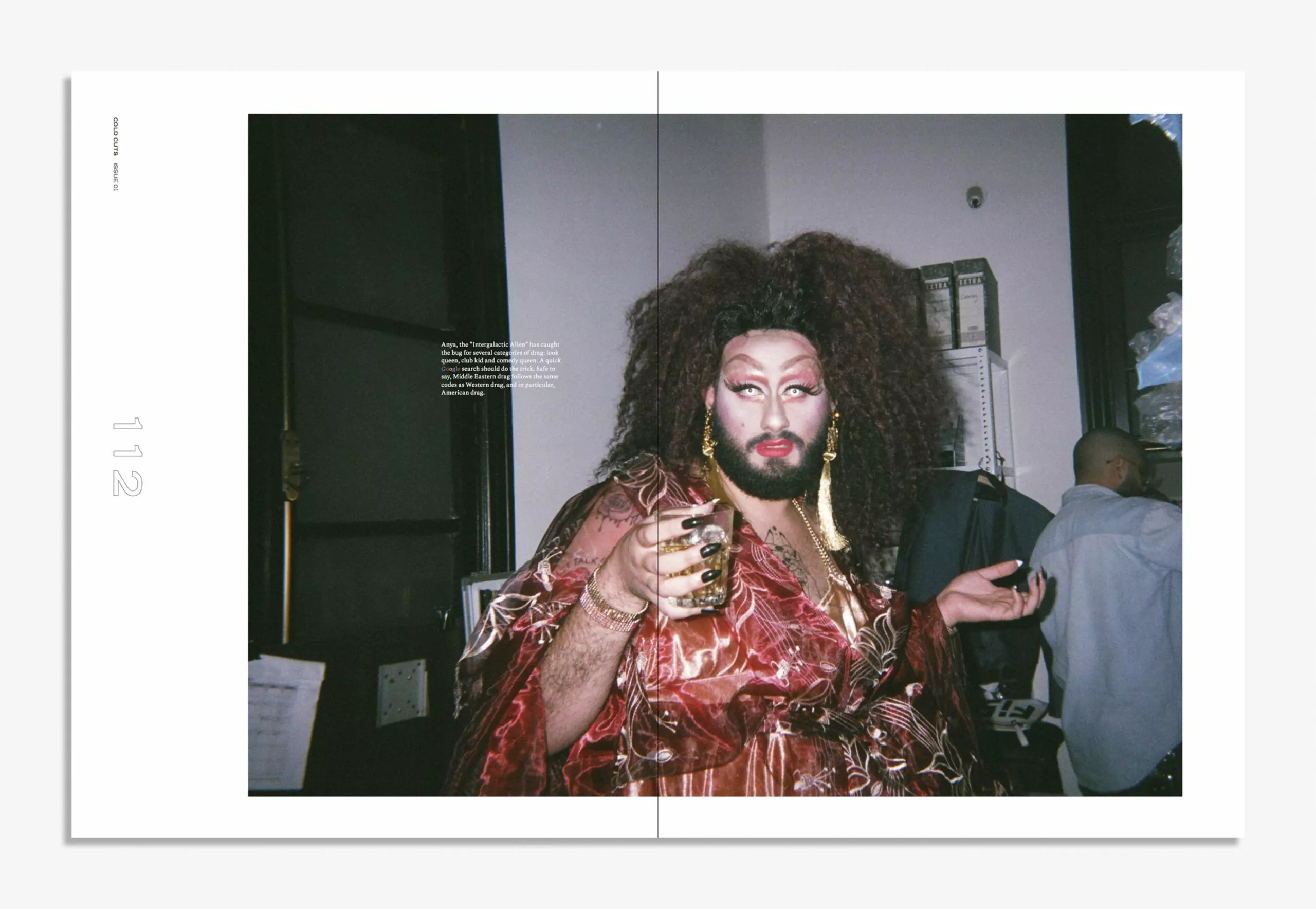

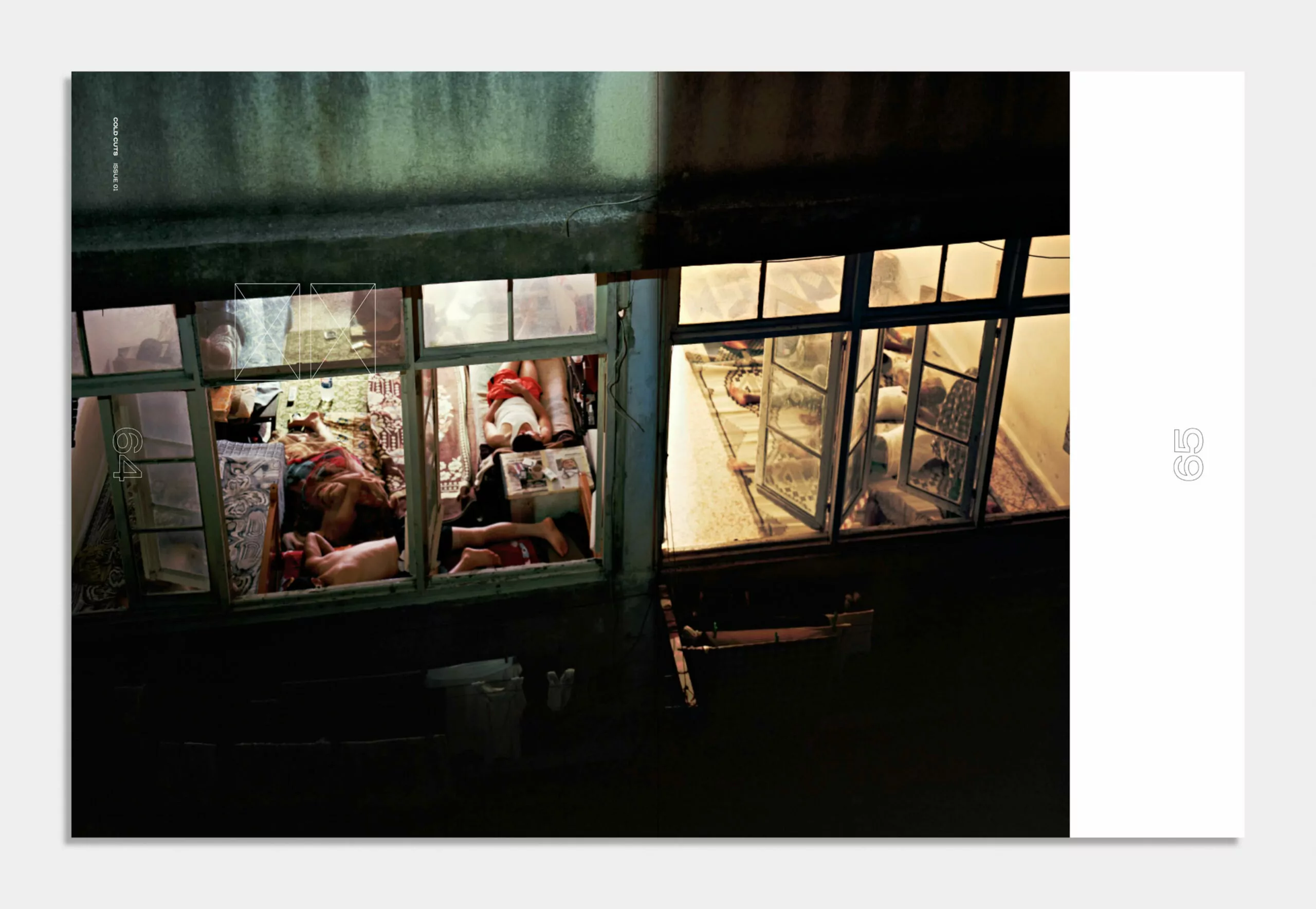

It started out with a curiosity to dig a bit deeper into our history as queer Arabs. I was very disappointed with the lack of documentation, and I just thought it was kind of unreal, and ridiculous that we don’t have proper documentation of our own culture. We just started off taking pictures of everyone and everywhere. We talked to people from all aspects of the community, from nightlife and personalities to DJs, activists, researchers, designers, musicians.

One part of the work that we do is purely documentation of happenings, events and the everyday life of the community, and the other part is more portraiture, and a more in depth look into the people that move our community further in one way or another.

What can a reader expect when opening up one of your issues?

Cold Cuts is essentially a photo journal that chronicles and documents queer culture in the Arab world. We feature photographers from the region and around the world that then create and document different aspects of our community, whether it’s Arabs in the region or Arabs outside the region.

What has it been like documenting the scene in Beirut?

It’s just not as dramatic as it’s portrayed in the media. Beirut is somehow lenient, not legally, but in a way, it is. Other parts of Lebanon are not lenient at all however. I can’t really answer the question without generalising, and that wouldn’t be fair. In Beirut you can do something and be revered for it, or glorified for it, and then you step out 30 minutes outside of the city and you can be murdered for the same thing.

What’s your overarching mission with Cold Cuts?

It’s pretty simple actually. It’s to document the Arab queer communities for future members of the LGBTQI++ community. It’s for anyone who is Arab and wants to learn more about their own history. As much as we go towards Western documentation, as much as we love watching documentaries like Paris is Burning, there’s only so much that we can actually relate to. At the end of the day, we’re not black boys from Harlem. Every community deserves their story to be told, something they feel like they can belong to.

Why is documentation of marginalised communities so important to you?

As much as we can relate to Western queer history, it’s still very different. The undocumented stories that we have of our own queer history are insane, beautiful, sad, exciting and interesting. When someone else is telling your story, they always have an agenda. It’s always talked about along the lines of “look at this glamorous drag queen in the middle of a war-torn country.” Which might be the case sometimes, but there are also other everyday things that are also extremely impactful. That’s why it’s important to document the community from inside the community.

Where can we find Cold Cuts?

The first issue can be purchased online or in Beirut at Papercut, and at the Beirut Art Centre. For the second issue, which will be released soon, we’re going to be distributed in several specialised shops in a few cities in Europe.