MILLE World is dedicating this summer to music and resistance. In this series, we will be examining the link between the struggles and the tones of the region. Each week we will be focusing on a specific country and unpacking the mystery behind their melodies.

Today we’re starting with Egypt.

Egypt is no stranger to music with a message. Throughout the years Egypt has bred the likes of Abdelhalim Hafez, Um Kalthoum, and Beligh Hamdy, adored by millions not only in Egypt but also throughout the region. Upon listening, one could think that the soul and harmony of these popular musicians embody the full spirit of modern Egyptian music and while that may be true, the rich rhythms reverberate and blend into a greater melody of international struggle and revolution which few have tinseled out from the beat.

Egyptian folklore songs have for centuries been not only a way to recall stories and tales from a bygone era, but also a way to communicate messages of strength and resistance during times of oppression, war, and even revolution. The spirit of the Egyptian people can be sonically documented through songs such as Patriotic Port Said, the song exclusive to Port Said and performed in a style named suhbagiyya, developed over 150 years, beginning when the town was first inhabited by Egyptian workers tasked to dig the Suez canal. Even this occasion was iconised by Azharite scholar and musician Sayed Mekawy’s Ommal Hafr Al-Qanal or The workers who dug the Canal in English.

Patriotic Port Said, being released after the repelled tripartite attack on the city in 1956 quickly found its way into the songbook of Egyptian patriotism, including being performed live by the band themselves in February 2011, in Tahrir Square. The memory of the tripartite attack was remembered best by Um Kalthoum, who sang “Three nations in arms, but none ever had a foot in Port Said”. Being recited throughout history, these are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Egyptian patriotism via the medium of song.

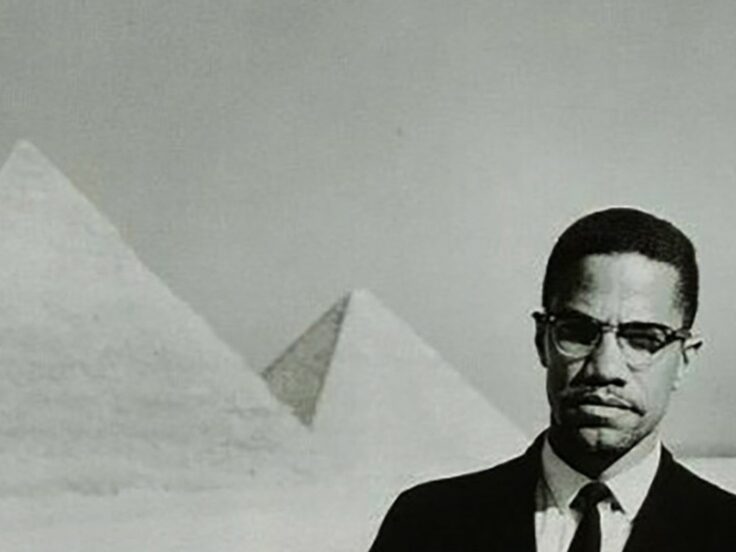

It is, therefore, not so surprising to trace a link between Cairo and Jazz music. In the 1950’s W.E.B. Du Bois, a prominent African-American pan-Africanist, founding member of the NAACP, not to mention the first-ever African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard, was barred from foreign travel by the US government. Gamal Abdel Nasser invited the then eighty-two-year-old scholar and his wife to settle in Cairo, offering them a home on the banks of the Nile, which they visited in 1962. Nasser announced solidarity with the African-American struggle and even began offering scholarships to black students in several prominent southern US states.

It was W.E.B Du Bois’ stepson, David Graham Du Bois, who best documented the link between the African American struggle and Egyptian sentiment at the time. He settled in Cairo in 1960, residing there until the 1990s, as an outspoken leftist, journalist, and professor of American literature at Cairo University. As his stepfather before him was one of the founding fathers of the civil rights movement, it’s not surprising to see a similar sentiment, and love of activism that saw him in the same circles as Malcolm X and Maya Angelou, even lodging them when they visited Egypt. Du Bois’s love of activism was only outmatched by his love of jazz, being a graduate of Oberlin Conservatory of Music, he extended the same offering to Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Sun Ra during their stays in the capital.

The parallel between anti-imperialism and internationalism becomes more apparent with the African American Civil Rights movement taking off in the United States, many people of African descent wanted to embrace religion – Cairo and Gamal Abdel Nasser’s new Egypt offered the perfect haven for revolutionary thought and progress.

As David Du Bois wrote in his book And Bid Him Sing that Cairo was ‘a sundry crew of Marxists, black nationalists, Nation of Islam and Sunni ‘Muslims’ who divide their time between local jazz bars, Al Azhar University, news bureaus, and ‘café-au-lait women’. Whilst all the while trying to establish a ‘progressive’ jazz culture in Cairo, helping newly-arrived expats who came to study at Al-Azhar, and also organizing gigs at local clubs.

The crossover between a post-colonial Egypt and the internationalist leanings of the civil rights movements at the time meant that Cairo was a perfect breeding ground for new ideas and sounds. The sonic embodiment of this is best represented by Salah Ragab’s Egyptian Strut.

Salah Ragab himself was the leader of the Military Music Departments in Heliopolis. Forming the first big jazz band in Egypt, with numerous members including many African Americans from the times of the Civil Rights Movement too. Their sound perfectly bridges the gap between East and West. If pan-Arabism and anti-colonialism had a soundtrack, this would be track one.

Massive thanks to @discoarabesquo for helping with this article.