As any kid growing up in the early 2010s, television shaped my views of the world, and my identity.

Let me explain.

I wasn’t merely watching the characters of my favourite series, I was falling in love with them and the worlds they inhabited. Even after the screens went black, my mind continued to be caught up in their fantasy.

Gradually, I began imagining close friendships with the characters I loved. I dove into worlds of illusions and made-up conversations. I even came up with entire scenarios and reenacted them, as if I were a character amongst them.

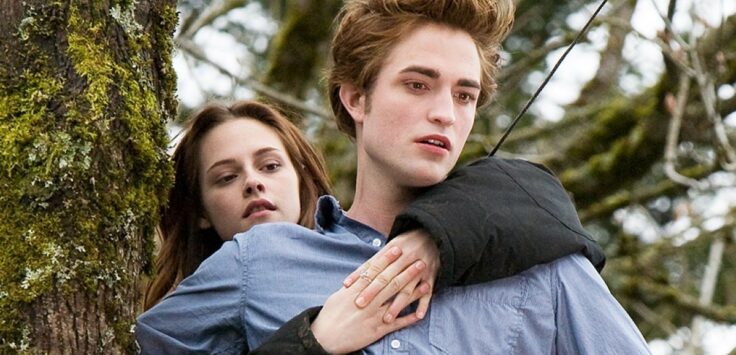

When the Twilight saga came out in 2008, the Cullen clan became my chosen family. I imitated the placidness in their speech and their mysterious manner of being. At some point, I was the eighth member of their family, joining their mission to save humans from evil vampires.

As I grew older, I picked up traits from every character I developed an interest in. I became an expert in their tastes, their manner of speech, and their traditions. That’s where the lines between their being and mine started to blur.

When MBC Action brought Supernatural to its catalogue in 2008, its lead Dean Winchester taught me American slang and idioms. That’s why a young Tunisian spent her teens telling her friends she doesn’t ‘give a rat’s ass’ and calling them ‘idjits’.

My English would also move from a Cockney accent which I picked up from Peaky Blinders to somewhat Scottish à la James McAvoy, and I even learned some Korean after the K-drama Boys Over Flowers had gone viral in the region in 2012—again, thanks to MBC.

I was aware of the imaginary line I’d drawn between the two worlds I lived in, but all the fun was had in the blurring of it. All the fun laid in escaping the reality of being a teenage kid that never fit in.

You might wonder if the reason why I was a misfit was in fact due to never truly setting foot in a single reality, but I had no interest in figuring that out.

I did learn that I wasn’t alone—and that there was a term that defined me and others who lived like me. It’s a phenomenon, and it’s called ‘parasocial interaction’.

It’s a “kind of psychological relationship experienced by an audience in their mediated encounters with performers in the mass media, particularly on television,” according to a 1956 study by sociologists Richard Wohl and Donald Horton.

It felt good to no longer be alone. I couldn’t be the only one to have experienced something so wonderful. Every new show or film that came out meant a new culture, new environment and new language for me to explore. But as I got older, the downsides became all that more apparent. Media is western-dominated, and I was delving deep into many worlds but my own.

The older I became, the more detached I was from my culture and reality. Slowly, I started to unravel sides of a colonial mentality that had been steeped in me solely due to a parasocial interaction that I might have taken a little too seriously. What else was going to happen with a lack of Arab representation and local narratives on television?

As I fantasized about friendships with my TV heroes and fell more in love with their identities, I deemed Europeans and westerners as the standard to look up to. I found myself constantly seeking out the presence of western social circles, all while living in an Arab country.

Whenever I’d meet a foreigner, I had this urge of wanting them to be a friend, exactly like I befriended the television characters of my childhood. I constantly looked to foreigners for validation. As I took steps into my twenties, the line between my parasocial interaction bled into real life to the point that it no longer existed.

Being a misfit eventually became a real problem. I’m not a multi-national nor have I ever lived abroad. You can say that I was bound to go through an introspective.

I couldn’t connect with others around me. Meeting people who were comfortable with their skin and Tunisian identity became a constant source of interrogation. Eventually, I no longer wanted to feel uncomfortable with where I come from and where I lived.

I hoped it hadn’t be too late. Despite being fictional, adopting the tastes of western television characters resulted in a real rejection of local arts and culture. Whenever in an Arab social circle, I looked down at the people around me. I compared real life get-togethers to a fictional television standard, but nonetheless, I felt home if western music was played, but not if the music were Arab.

I once found comfort in not being alone in my parasocial interaction. Today I seek unity in fighting against the homogenization of taste—and it all starts with a balanced, diversified internationalism, not globalization in favor of one culture.