Globalization has long been taking effect and identity politics have very much become a topic with great importance to many of us— particularly Arabs living in the west whose identities have stripped and deconstructed by certain (not always positive) narratives.

As is the case for photographer Walid Layadi Marfouk, who, after moving to the US for the first time became exposed to perceptions of the very Arab and Muslim identities that he had never experienced in his native Morocco.

But for most people, making sense of this inner conflict can be difficult– especially for those lacking a medium to sort it through. For Layadi-Marfouk, photography became his chief outlet. Wanting to reclaim the ways in which his ethnic and religious identities were represented, he began constructing visual depictions of what he believed was an accurate portrayal—similar to the way African filmmakers did in the 60s and 70s as a form of rejecting the typically imposed colonial narratives.

After moving to the US to study at Princeton, Marfouk embarked on a photography course (just so that he could fulfil his requirement for his Maths and Engineering degree), and this is where he was first introduced to the 4×5 camera. He immediately fell in love with the large format camera, firstly because of the technique it required—telling us “the physics—the optics— of operating the 4×5 immediately had an allure like nothing else… The technology is rudimentary, but it allows you to build images that are all the more complex, precise and immersive”.

And thus he had unintentionally begun his journey as an artist, creating beautiful photographs that have since landed him on the walls of the new Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL) and the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair.

MILLE caught up with Walid to talk about his beginnings, Muslim representation in the west, and why his photography might be difficult for a Westerner to interpret.

How did you get in to photography?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always had this urge to create, whether through manual construction, or writing and storytelling. Before this class [at Princeton], however, I lacked an appreciation of what really drove this inherent tendency, I didn’t have a genuine sense of what I wanted to, or needed to express, intimately. I also lacked the tools to manifest this instinct in its purest form.

What would you say is the biggest motivation behind your work?

It all started after I moved to the U.S. I realized I was entering an environment where the outlook on Islamic culture felt extremely uncomfortable. Almost ontologically so. It took me a while to understand that the issue was not only one of factual misinformation, but also one of representation.

Ever since the nineties, the Muslim world has almost exclusively been documented in contexts of violence, extremism, desolation, poverty, war etc. When you look at recent Western imagery of the Middle East or North Africa, colonialist and orientalist imagery have given way to flat, black and white portrayals. Ask the average American or European about Islam and the first image that pops into their mind is likely that of an unidentified dark veiled figure in a starkly deserted and sandy ruin.

These images have become so prominent that they have dwarfed all other facets of Muslim culture and spawned a brand of fear and rejection we are all too familiar with. Knowledge and attitudes towards Islam have been patterned by exposure only to extremes, and it is in this context that I understood what my role and that of the Riad could be.

In your series, Riad, you exclusively feature your relatives as your subjects, why is that? How did they feel about being part of your project?

Everyday, as I work on my practice, I think about my own legitimacy to hold a discourse on an issue as intricate as that of the representation of an entire culture. I spent months doing a deep dive on representations of women, particularly in the Arab world, but I am only 22! So I decided to explore my family’s history, my own heritage, because that’s the one topic I know thoroughly.

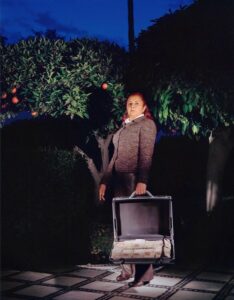

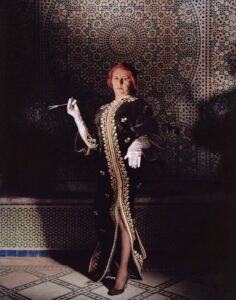

Photographing my relatives in the house of my great-grandfather in Marrakesh, where they all grew up, allowed me to develop a new, intimate visual language. In that, the works are very subjective, and carry no overbearing pretences. The goal is to convey a slither of Moroccan culture the way I perceived it growing up — and still do today.

I get the vibe that your photos are extremely thought out and everything has been meticulously curated. What’s your creative process like?

Every element in each photograph in Riad is sourced from my family. The caftans all come from my mother, my aunt or my grandmother. The furniture and the props come from my grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ houses, which grounds the works in their authenticity. Conversely, every scene is entirely constructed, from the décor to the poses and the subjects’ facial expressions, and that staging and theatricality is meant to displace them from the realm of documentary photography.

The lighting is also an important device in the displacement strategy. I use halogen lights that were commonly employed on movie sets up until the 1930’s to create a cinematic nostalgia of that time, and further displace the scenes in time.

The resulting images are sometimes surrealist, and they don’t claim to supersede reality, but they always reject Western orientalist and paternalist tropes. That can sometimes make the images harder to decipher for the non-oriental viewer, but that is part of the point. It is a way to claim back some agency in the representation of my culture.

What can we expect from you in the future? Any upcoming projects you’re working on?

I am always striving to further and promote cultural empathy, through any appropriate and relevant avenue. Currently, I am working on a book project that focuses on just that, with a former Princeton professor of mine, Rachael Ferguson. I’m also researching my next photo series, which should be completed this fall.