Cinema—and society—is still overwhelmingly male-dominated. But thanks to social media, women are creating supportive spaces challenging the patriarchal structures that rule the industry, and celebrate female art in the process. 19-year-old Irish-Iraqi Róisín Tapponi, founder of Habibi Collective, the IG account celebrating cult feminist films, is one of them.

Tapponi spent her childhood obsessively consuming films on her own – sitting on the hard floor against a radiator with a blanket “because the Wi-Fi didn’t work in my bedroom”, she says, until 2015, when she finally to realised that she was barely watching any female-lead movies.

That’s how Habibi Collective, her visual archive project, and Instagram account that celebrates feminist films from the Middle East came about. “Middle Eastern is a Western term”, she says before adding, “so many artists today are both Western and Eastern, and the plurality of this co-existence, crossover and double-presence was something I was keen to explore”. Despite the designation “habibi”, Tapponi’s work goes beyond the borders. She’s inherently fascinated about globalization and its effect on people and culture, she looks at the role films play in a hyphenated world and “how artists can respond to the sense of up-rootedness”, she explains.

But what Tapponi is obviously most passionate about is how cinema interrogates the female gaze. She naturally felt that it was her duty to “brush history against the grain”, by putting a spotlight on the region’s cinematic history. There is a wealth of incredible female actresses in the Middle East, like Soad Hosny for instance. But if I can recall correctly, she appeared in at least 80 films between 1959-91 and not one of them were directed by women”, she says. The first female director that she looked in to was Moufida Tlatli, the first Arab woman to direct a full feature-length film in the Arab world, and the first director she ever shared on Habibi Collective’s Instagram page.

MILLE caught up with Tapponi to find out the five most important feminist films from the Arab world.

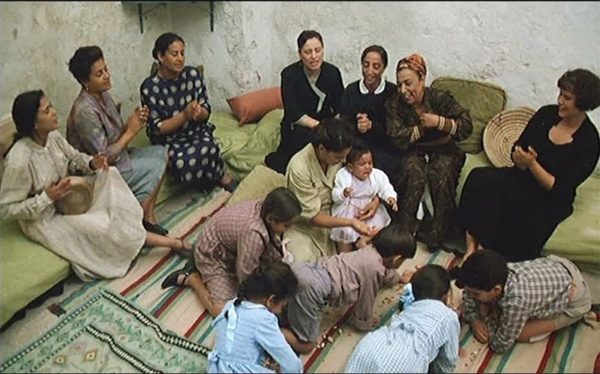

The Silences Of The Palace – (1994), Moufida Tlatli

“A beautiful film by one of the Middle East’s greatest. This feature exposes the sexual and social servitude of women in a palace during the French Protectorate in 1960s Tunisia. I think this film is important because it gives a critical voice to women who throughout Middle Eastern history have been aborted and silenced by their husbands. Like Mai Zetterling’s The Girls (1958), which follows three Swedish stage actresses re-writing the classic Aristophanes play Lysistrata, and Věra Chytilová’s super fun Daisies (1966, which establishes Czech cinema as critically relevant within the New Wave movement, it allows women to revise their own role whilst looking awesome at the same time. Plus, the soundtrack is banging and it stars the super talented Ghalya Lacroix, who also wrote Blue is the Warmest Colour!”

Persepolis – (2007), Marjane Satrapi

“This is the first Middle Eastern film I remember really being picked up by Western youth culture, or by the town I was living in at least. I think Persepolis is important because it is not the story of a punk-loving girl wanting to escape her country, but rather yearning for her beloved country to return to its more liberal days pre the Iran/Iraq war. I also love the crossover between cinema and graphic art (and punk music), Satrapi also being a prominent graphic artist. This cultural and fusion of mediums is important because it contributes to what one of my idols Laura Mulvey tried to establish in 1977 by striving to create a female-specific film language with “Riddles of the Sphinx”, and what choreographer Pina Bausch (one of my other greatest idols; I actually have a shrine to her in my room) tried to show in her 1990 dance film “Die Klage der Kaiserin”. That, cinema is a medium for a women to experiment with through a plurality of artistic lenses, and that it is now finding its footing in the mainstream.”

Scheherazade’s Diary – (2013), Zeina Daccache

“Ackerman was one of the only female filmmakers I knew. The theatricality of her performance opens up a discourse between theatre and film, which is more developed in Deccache’e Scheherazade’s Diary, where Daccache records the rehearsal process of Arabe female prisoners. This amazing documentary looks at the quotidian of female Middle Eastern prison life, and how theatre for female prisoners can be used as a productive force.”

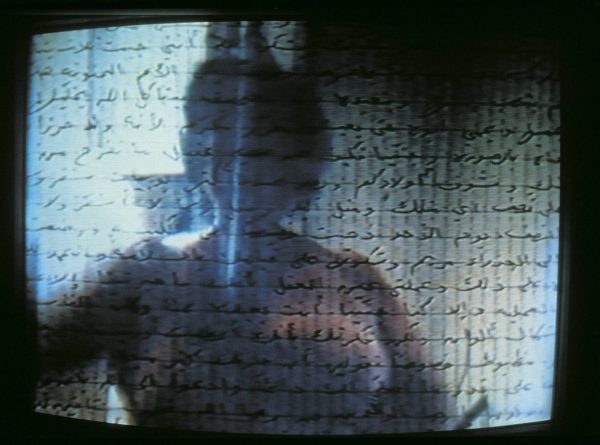

Measures of Distance – (1988), Mona Hatoum

“A groundbreaking short film by performance artist and sculptor Mona Hatoum. The audio weaves conversation between Mona and her mother, her mother speaking openly about her sexuality and her husband’s objections to Hatoum’s intimate filming of her mother showering. What the viewer receives is a window into an extremely close mother-daughter bond, whilst also touching on the framework of displacement, disorientation, and exile. As written by Hatoum in Mona Hatoum 1997, “In this work I was trying to go against the fixed identity that is usually implied in the stereotype of Arab woman as passive, mother as non-sexual being. The work is constructed visually in such a way that every frame speaks of literal closeness and implied distance.”

Tell Me The Story of All These Things – (2016), Rehana Zaman

Several narrative threads draw together intimate conversations between the artist and her two sisters, as Zaman’s experimental work challenges power structures through a sensory approach. This is about activating the female agency through moving image practises, and celebrating female pleasure through honest conversation between three women.”