The Wright brothers, Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm, the Jackson Five — history books are full of famous brothers who made an indelible mark on humanity and influenced generations that came after them. Whether they built and successfully flew the first motor-operated airplane or gave us enduring fairytales like Cinderella and Rapunzel, history’s most revered siblings undoubtedly changed the world with their talent and genius. Joining the list of acclaimed brothers distinguishing themselves and making an impact in their wider community are Abdulrahman and Turki Gazzaz.

The Saudi architect duo are one of the region’s most profound figures in the discipline of architecture today. Having co-founded their own multidisciplinary practice and joint collective Bricklab in Jeddah in 2015 after stints at renowned international firms, the Gazzaz brothers are leaders in meaningful and impactful design. In 2018, they were commissioned to design the pavilion for Saudi Arabia’s long-awaited debut at the Venice architecture biennale; and a year later they were awarded the winning design for Art Jameel’s independent picture house, Hayy Cinema. Their diverse work has been exhibited internationally, including at Salone del Mobile, Art Dubai, and Shubbak Festival.

In addition to being architects of buildings, Turki and Abdulrahman are also creators of community, viewing their designs as a by-product of a greater end. Using their creativity as a tool for change-making in society, the dynamic duo puts people at the core of every project. In 2018, for instance, while developing the design for Hayy Cinema, an audiovisual center in Jeddah, they went out and spoke with directors, actors, and casting agents to truly serve the communities that will use the space most. To them, architecture is about contributing to society and speaking to and for the people it serves.

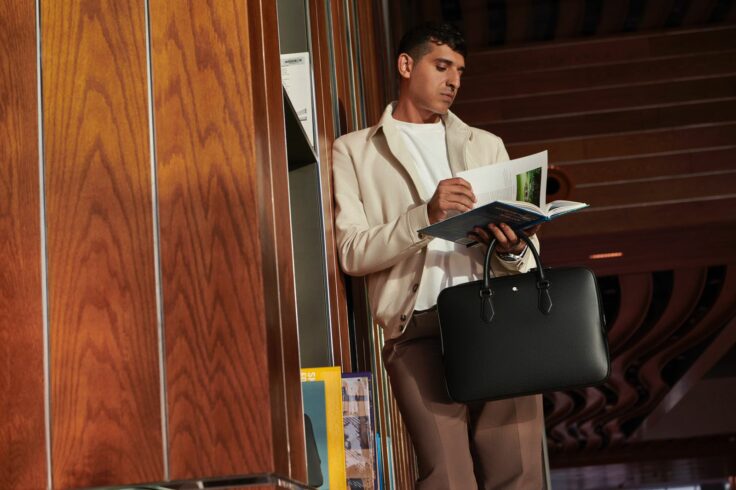

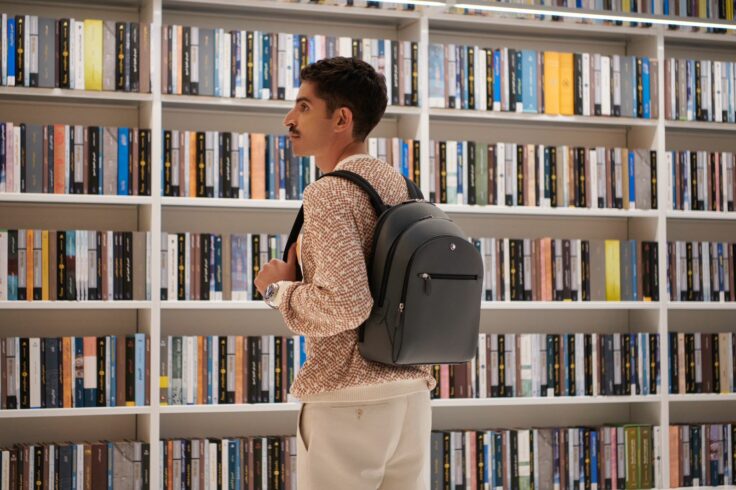

The design duo’s thoughtful and layered community-led approach to design is reflected in almost all of their lineup of projects, including Saudi Modern, an initiative that sees them archive and restore old buildings that are disappearing. But their portfolio extends well beyond just impactful designs. The brothers recently caught the attention of luxury German house Montblanc, which tapped them to star in its newest campaign for Ramadan alongside Emirati actress Mahira Abdelaziz.

To get to know them better, we asked the brothers a few questions to delve into their practice and the role played by architecture as a tool to paint a vision of a better future.

You guys have done some really cool and incredible projects, like the first Saudi pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Is there a certain project that you’re particularly proud of?

Abdulrahman Gazzaz: Architecture for us takes on different scales. Saudi Modern is an initiative that we worked on that archived buildings that are disappearing. I think that was quite impactful. It took place in Tamar House, which is owned by the Tamar family here in Jeddah. That family wanted to tear down the house, but we went up to them and we told them we want to do an exhibition that showcases architecture and the house would be the main art piece, where we do a very light restoration to the structure and change the use from it being residential to it being a gallery space. Even before we wanted to open it, the family were thinking, we’re going to do this one time thing, and we’re going to tear everything down and rebuild it.’ But once they saw the exhibition and once they saw the space, they decided to keep it the same and just to keep using it in different ways. And I think that is a prime example of how architecture can benefit the areas around it, how it can benefit people, and how it can kind of be shifted and changed.

Leading up with that is also our work in the JAX District. It was one of the first projects in JAX. We had to restore about nine or 10 warehouses. We studied Wadi Hanifa, it lies next to it, and kind of abstracted the colors, the techniques of building, and how our intervention would be within the space in close coordination with the sonography team and the artists.

Turki Gazzaz: I don’t think you mentioned the Hayy Cinema project. It brings together a lot of the different aspirations and a wider community involvement that we have in mind with each project. So the whole idea of our design proposal was to not only provide a cinema screen, but also provide an audiovisual center in Jeddah. We identified that there is a gap in the market for this kind of space. As we were developing the design, we went out to different members of the film community and spoke with directors, actors, and casting agents. This was in 2018, so these kind of facilities that we had was very limited at the time. We asked them questions like what do you want? What do you think the community needs? We did almost two months of these back and forth interviews. And what we ended up with was not only the cinema screen, but a community screening room, an archive, a library, and a café. Once the cinema opened, it was really interesting to see how it also started to create a community around it. It wasn’t just films— there was smaller screenings, an exhibition of the Youssef Chahine movies. There is obviously the aesthetic part of the design, what kind of colors, what kind of materials we use, the lighting. But then it’s amazing to see that added element of that space being used and seeing that community starting to form around it.

You’re architects of communities. Can you tell us a little bit more where you see yourself in this wave of new architects that are all-encompassing and using architecture as a vehicle for community and patrimony as opposed to just architectural objects?

AG: It’s interesting that you ask that because it also asks the question of architectural monumentality for us. We critically question the very reason of why this project is the way it is. Even when clients come up to us and say, ‘oh, I want a modern building here, or I want this there’ we always look at the context. We always look at where it came from, what do we need, what is the brief? And we always even challenge the brief. We’re like, no, we actually, this needs to be implemented in that particular way because we believe in that. For us, it’s more about this experimental approach that creates a feeling of monumentality. Architecture is something that ties to your senses and your memories, and how can you either embed a memory or remind someone of a particular memory given the particular atmosphere or the view they’re looking at, or where they’re situated, what they smell, what they hear, what they see. I think with that, we begin to scrape the surface of what are the technologies that we might need to be able to sustain that particular character or to insinuate that particular feeling within a visitor or someone who is inhabiting that space.

TG: If there’s anything to add to this, we really believe that architecture plays a very important role in not only our understanding of identity, but our understanding of place. It really creates that kind of world. And for us, it’s really important to be sensitive to the specificities of each site, to the people who are using it, and to create meaningful interactions with architectural form and details. If you compare it maybe to the larger scale developments that are happening in other parts of the GCC, I think these are less interesting for us because sometimes when the project gets too large or the developer and the user are very disconnected, you end up designing something for someone without knowing who is going to end up using it. And sometimes, you don’t even know what the site is like or how it connects to the rest of the city.

What’s the dynamic like working with your brother?

AG: I think it’s great, to be honest. It’s very easy to communicate, to work on things. Whether each person is handling different aspects, we still understand the approach of one another. And I think also for the rest of the team, they share that same vision and they take that into completion as well. Sometimes we have an opposing point of view, but that’s what keeps us interested in our projects because we all keep challenging each other on different things. We really critically question the very reasons why we’re deciding on this particular concept. Why does it look like that? Why is it framed that way? Should we change directions? And it’s always through these conversations that the project takes form. Obviously a lot of research stems from that, but I think we even used the research to convince one another that this is the right direction for that particular project.

Growing up, did you always have similar interests? Did you think you would end up working together in the future at some point?

TG: No, we ended up working together purely by coincidence. Up until we started university, we had different interests. Obviously, our household has some creative tendencies. My older sister is an artist. My father wanted to become an interior designer, but at the time, it wasn’t one of those professions that were supported. And so to compensate, he was always into collecting antiques. And every year we had a different renovation project around the house. Growing up, we also moved quite a lot because my father was really interested in design and experimenting with different spaces. He was always looking for the perfect house so we just kept moving. I think we moved, what, 12 times?

What inspired you to pursue architecture as a career?

TG: I was always into playing with Legos, or making things. From an early age, I was inclined towards drawing and putting stuff together. When it came time to choose a major in university, I was like, okay, I think architecture makes sense.

AG: You end up going into university, not really knowing what’s going to happen next. So for me, I went through so many different things. I’ve gone through photography, sculpting, graphic design, marketing, and engineering, until I found myself in architecture. Throughout that whole process, I gained a really deep interest in architecture. So going into it, I was really, really fascinated. I had actually gone into architecture I think two or three years after Turki went into it, although I’m older. We never really thought about starting our own studio or doing our own thing… I mean, life happens and things take form in a completely different way.

Speaking of the studio, Bricklab has obviously grown extremely rapidly. Do you have an end goal in mind?

AG: I don’t think that there’s a specific end goal, but I think that our ambition is to make a contribution to the built environment and be able to give back something to our city and the local community.

TG: It’s really just to make things better. I mean, with every project there’s a different topic of research, so we gain a better understanding of the context, whether the context around us or in any other places.

Let’s talk about your partnership with Montblanc. You’re both the latest additions to the family as brand ambassadors, and I was just wondering, as trained architects, what is it about the world of luxury and working with Montblanc that interests you?

TG: As for the world of luxury, I’m not sure I can give you an answer, but with Montblanc in particular, as a brand, it is very in line with some of our values. This idea of going back to using the pen and relying on the hand as a way of designing and a way of thinking is very interesting. With computer-aided design, a lot of people can actually design full buildings without knowing how to draw a simple cube on paper. But I think that the use of the hand isn’t out of fashion. It’s scientifically proven that there’s certain sensibilities that are explored using the hand that cannot be replicated in the same thought process as the computer. And Montblanc has great pens.

Sustainability is also an important value to Montblanc, which I know is important to you guys as well.

AG: I think sustainability is a very malleable subject. For us, in terms of sustainability, instead of going really far, who is the closest craftsman that can make this? Or how can we manufacture this within walking distance, let’s say? It’s also about social sustainability. How can this particular project provide jobs? How can it provide a walkable environment? How can it create wellbeing for the people who are living around it? How do we embed a particular architecture within a socially sustainable place that does not need to be redone? So we believe that architecture is something that is subject to decay and time, as all things are, but you can always reuse certain elements. We really look at that through our various travels going through modern architecture and ancient remains and questioning how these are made and what made this particular civilization or particular era in time something that’s fascinating now. And how can we really appreciate the moment that we live in today? Then that kind of really informs the material aspect of a given space within the overall architecture. If I want a 3D print for 3D printing sake or a glass box for a glass box sake, it’ll be a reaction to something that is needed and something that can benefit the users and the area around it. It’s almost like this butterfly effect, like, we do one thing and see how it can benefit many other things at the same time.

How do you balance the desire for sustainability with the need for functionality?

TG: I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive. In an ideal world, they should be very complimentary. I think the idea of sustainability has recently been really narrowed down into these very restrictive lists or certifications that you get from international organizations that lead the sort of ‘green certificates’ that you get for buildings. But at the same time sustainability is not just about the material and the social sustainability of the building. It starts off from how the building is commissioned all the way until it gets completed and used. So when you think of sustainability this holistically, then sometimes you would use materials that could be not sustainable by the book, but really produce a great impact on the people using the building. So it just asks the question of how do you define sustainability today? And how can it move beyond just the fashionable set of materials that are being advertised today as being very sustainable? As architects, we only play a certain part in that process because I think a lot of it also goes back to the industry and what kind of materials are available. So we often find ourselves at a point where the sort of sustainable options do not meet the client demands or do not meet the project budget. So it’s either, the whole kind of space becomes compromised or we just use conventional materials to make it a reality.

You’re very much into the history and the local aspect of what you’re doing within the people and the usages. You look back and create a better future with what you have as opposed to bringing some internationalized standards of what the landscape could look like.

AG: I think that’s really important. It’s something that’s usually kind of misread in a way where people think that we are nostalgic towards the past, but history is something that is that is ongoing. Yesterday is a part of history. So we not only look at the past that gives us this particular identity that the audience is usually used to, or visitors of particular buildings are used to. We dissect the very identity of the entire area. Who is living in it now? How is it being used now? How can we make it better? Or if it wasn’t used very well, how can we create a possible future for it? Also on the completely opposite side, maybe in the past that area was so much better because it had more open spaces or something like that. So do we start introducing a public space within the building to resonate with that and to remind us of how we can learn from the past, but also we can recreate the possible future? We don’t own a particular history and our interventions are always subtle to the point where in the future if someone wanted to change it they could easily without harming the structure and integrity of the building, or the identity of the building.

Can you speak a little bit about the majlis design you did for Montblanc’s campaign video?

TG: For the design of the majlis, we really looked at the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum library. We were inspired by the library and the multitude of the books that were there, but also the basic premise of the space. The books in a way almost become a palimpsest that becomes a gateway for the reader to explore different modes of knowledge. We wanted to introduce a very subtle, and almost invisible piece of architecture, and that’s why within the design we decided to carve into the floor itself. As a very abstract indication of carving into stone or cutting into paper, the architecture becomes an imprint within the space itself and the reflective surfaces are a way to create a mood or an atmosphere. We really wanted to do something that is very comfortable to occupy while reading a book— I’m talking about it as if it’s an actual project.

AG: If it was actually in the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum library it would have been a place for social gathering and perhaps a very quiet conversation about a book and that’s why we really wanted to go for something very simple.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.