The German capital is playing host to one of the country’s largest creative gatherings, currently underway until September 18. Droves of artists and enthusiasts flocked to the 2022 Berlin Biennale to showcase their own works, explore those of others, and experience an event to remember — and considering some of the circumstances surrounding the three-month-long event, it surely will be the case.

Three Iraqi artists, Sajjad Abbas, Raed Mutar, and Layth Kareem, recently made the decision to withdraw their participation from the 12th edition of the esteemed exhibition. In a lengthy statement posted online, the trio claimed wanting to protest against the inclusion of some photographs depicting real-life prisoners being tortured at Abu Ghraib Prison at Biennale.

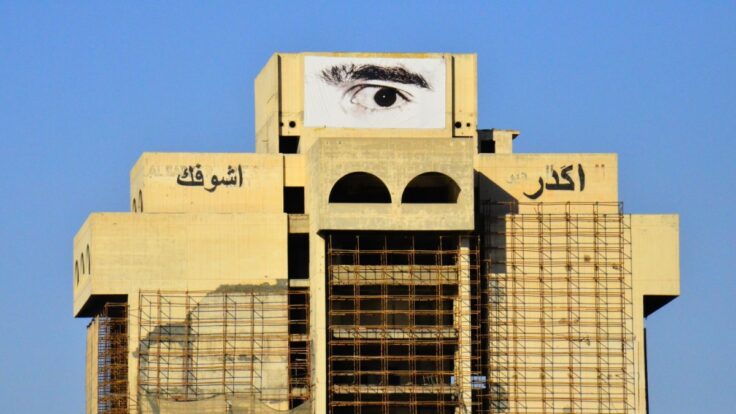

Located west of the capital city of Baghdad, Abu Ghraib served as a maximum-security penitentiary where torture and weekly executions were seen as a regular occurring. Opened in the 1950s, many members of the US Army and the CIA repeatedly violated the most basic human rights, notably through methods of physical, moral, and sexual abuse against illegally detained convicts and especially during the war on Iraq.

The controversy heavily revolves around Jean-Jacques Lebel’s Poison soluble, which reproduces pictures taken by soldiers, at the said prison, one year after the United States invaded the Middle Eastern country as part of their pseudo war on terror. According to reports, the French artist “printed and enlarged the color snapshots taken by the torturers, interspersing them with black-and-white press images of Iraqi towns devastated or completely obliterated by the U.S. Air Force.”

Naturally, once aware of Lebel’s participation at Berlin’s Biennale, Iraqi curator Rijin Sahakian released a statement, co-signed by the above mentioned artists as well as 400 other supporters, affirming their withdrawal from the event and detailing the reasons and incentives behind such move.

“The works we shared with this Biennale were made in Baghdad in the aftermath of, and in resistance to, US-led wars and invasion. We have a right to contest the curatorial actions of the Biennale without it being described as a ‘fight.’ This is a tired way of painting Iraqis as unable to engage in liberal humanist values and has been used by the coalition to deflect blame for the war’s massacres and failures. Here, it is invoked as a teachable moment. Asking for the responsible handling of criminal evidence of war crimes is not a form of erasure, it is the assertion of a collective Iraqi voice against the perpetuation of the occupation’s violence,” Sahakian wrote.

“The curator’s artistic practice and personal family history taking precedence over the artistic practice, lived experience, and family histories of Iraqis speaks to the asymmetric power this biennial is intent on producing in its discourse and in its curatorial negligence. In an exhibition that prioritizes the display of wrongly imprisoned Iraqis photographed in the act of being sexually and physically tortured, no, we do not find sincerity or transparency in this paternalistic response,” she added.

In a statement issued 17 August, the Biennale team replied: “We respect the artists’ decision, although we regret it very much. We believe in dialogue and value the relationships we have with all artists taking part in the Berlin Biennale very much. We are still interested in working through the controversy and will remain open to a dialogue. We think the issues at stake are highly important and would therefore like to invite all parties involved to speak about them in a public discussion. More information on this will follow soon.”

The works of all three artists have now been removed and moved to other dedicated locations for arts and creative expression.