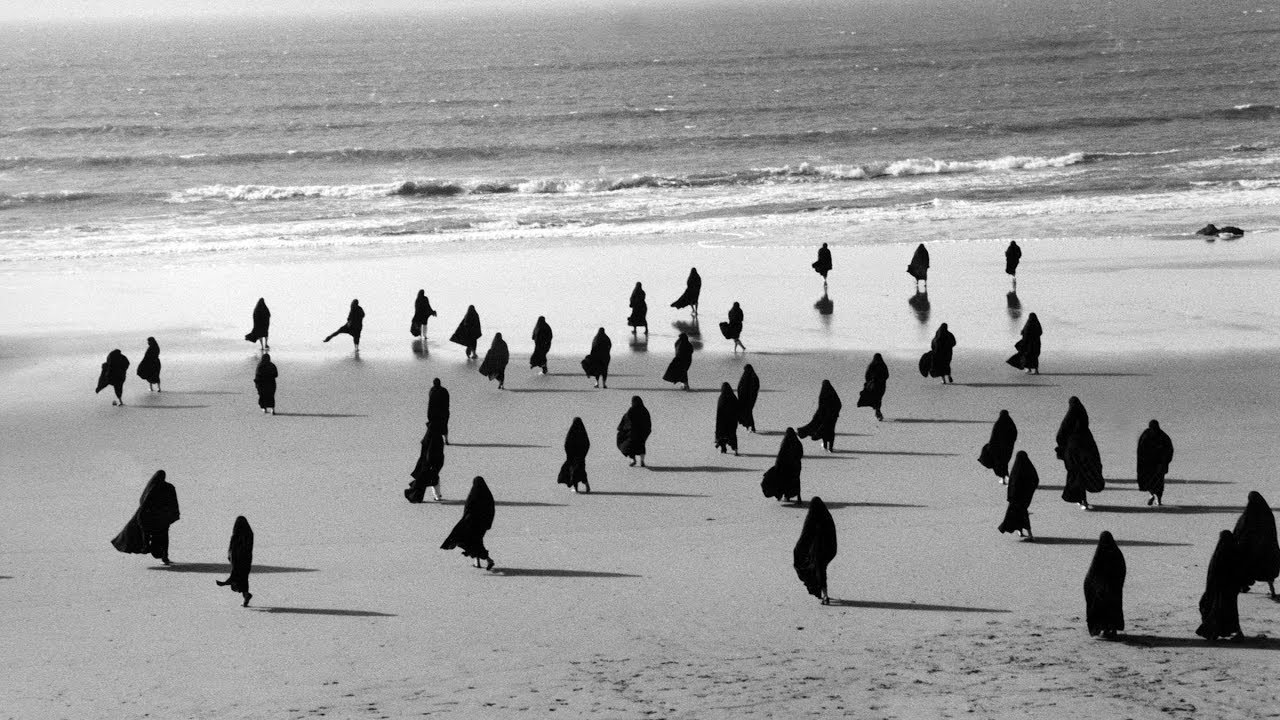

Even beyond the Middle East, Shirin Neshat is a household name in the contemporary art world. Working across film, photography and video, she arguably first achieved international acclaim with Rapture (1999), which addresses the relationship between women and the cultural value system of Islam.

Born in 1957 in Qazin, Iran, Neshat left to study at the University of California at Berkeley, on the cusp of the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Her earlier work, the Women of Allah series, looks at the intersections of gender, identity and society, particularly poignant at a time when Middle Eastern (and especially Iranian) society disintegrated under the politics of war. Her split-screened video Turbulent (1998) won the First International Prize at the Venice Biennale and she later won the Silver Lion for best director at Venice. Since then, her work has earned major exhibitions at MoMA and the Tate Modern among others, and Huffington Post has named her Artist of the Decade.

Apart from popularizing art films in the Middle East, creating, living and working outside Iran, Neshat has been influential in the optical emergence of diasporic art. This hybridity, alongside the juxtaposition of her visual art, has influenced a wave of contemporary Middle Eastern artists who have left their native countries. Speaking to filmmaker Maryam Keshavarz, she recalls meeting Neshat when she first emerged in the New York art scene, “I love her work, she’s operating on another level. I remember seeing Rapture and thinking ‘Oh my god here’s a woman who is not living in Iran but taking those memories and visualizing them, sounding them; that is so visceral and moving beyond the narrative’”.

Whilst Neshat’s contribution to the contemporary art world is undeniable, how do her portraits of gender and religion relate to our increasingly fluid and shifting notions of identity today? As Neshat’s work has recently been criticised for increasingly catering to white middle-class MoMA audiences, how does her work reflect and represent our current Middle Eastern audience?

Firstly, Neshat’s work continues to be politically relevant. For example, she recently created work for non-profit Planned Parenthood’s collaboration with art producer Tanya Selvaratnam entitled ‘Unstoppable Art’, a campaign rallying reproductive rights with class and ethnic rights. Commenting on the inclusion of her archival piece Soliloquy to ArtNewspaper, she said ‘“I couldn’t be more pro-choice. I absolutely believe on an international universal level that women should have the freedom to choose what they want to do with their bodies”.

Not only concerned with contemporary politics, Neshat’s historical awareness has recently taken a revisionist position. As shown in her most recent film Looking for Oum Kulthum (2018), Neshat shows an agenda to rewrite women into dominant historical narratives within Middle Eastern culture. She also participated in Tate Modern’s highly acclaimed Soul of a Nation exhibition (a travelling show examining current race relations in the US).

Since the 90s Neshat has been at the forefront of the art industry, and as shown by the sheer amount of work she continues to produce, her engagement with socio-politics cements her dynamic legacy in the contemporary art scene.