Whether from Morocco, Egypt or Palestine, Arab rappers have been on the come up over the last few years – and while that’s been a cause for celebration for most, DJ Sotusura says that this ever-popular iteration of auto-tuned trap isn’t his thing.

“It’s a new form of hip-hop” he says. “It is what it is. I don’t love most of the stuff I hear. I feel like the rapping element is out. There isn’t a lot word play. The ones who are lyrical, I respect. But not the ones who are more on the trap singing tip.”

With his old-school influences in mind, much of his outlook doesn’t come as a surprise. He lists Wu-Tang Clan, Public Enemy, and Michael Jackson amongst them, alongside Arab greats like Oum Kolthoum and Fairuz, whose music he didn’t appreciate until later in life.

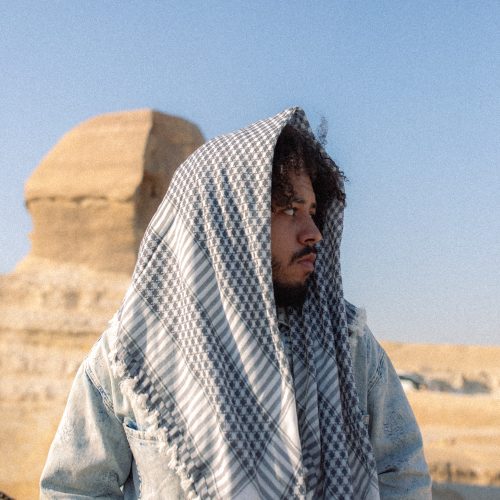

The 38-year-old France-born Palestinian DJ has been in the music game for a few decades now. Having bought his first turntable in 2003 when his cash-strapped neighbour decided to sell his, he’s made a name for himself in Amman and across the Arab world, pioneering the regional hip hop scene alongside Palestinian collective Ramallah Underground that saw its rise in the early 2000s.

“The scene back around 2004 was small. There were hip-hop nights in clubs. They were frequent but not regular. And at the same time Ramallah Underground and DAM came out, and that pushed local rap to start coming out too. It was kind of the beginning of it all,” he says, reflecting on the early days of hip-hop in the region.

Today, he spends most of his time in Cairo. And despite his disdain for the majority of hip-hop coming out of the Arab world, he’s still very much involved in the scene, not only DJing but releasing music of his own for the first time.

His debut album Saleh Elalhan dropped in March, and the same classics that influenced his take on contemporary Arab rap are evident in each of the 16 instrumental tracks.

“It’s kind of the natural progression of things,” he says when asked about why he’s only now releasing his own productions. “Producing gives me a certain kick that DJing used to give me,” he explains.

After a listen, it’s evident that the album is the product of years of digging up sounds from across the world. “I’ve collected records for a really long time. When I lived in the US I started to buy hip-hop records. Then I moved to the Middle East, and I started collecting Arab records.”

As a result, the album is a unique amalgamation of both, and to him, the inclusion of classical Arab sounds is most important. “Until I was 13, the only Arabic music I heard was inside my house. That’s the stuff all of our parents listened to. We all heard it growing up, whether we liked it or not” he says. “I wanted to start with that. It was all about the process of going back to it, and listening to it with a different ear.”