I’m anything but a music buff. Despite my compulsive itch for blasting music throughout almost every hour of my work days (which is probably causing my short attention span and getting me in trouble at work— we’ve all been there), I still consider my sonic knowledge to be very humble, to say the least. So why am I writing a full-length essay on North African jazz? Maybe it’s my underlying know-it-all-like desire to be (or at least sound like) a music expert. Let me explain.

I had just reunited with an old high school friend of mine and without me knowing I was in for a little history lesson. Forever a music geek, she shared with me one of her playlists which she dubbed “Jazz el Casbah” (a pun on English band The Clash’s Rock the Casbah— minus the obviously racist connotations of the song—and Algerian musician Mohamed Rouane’s Casbah Jazz tag).

As intriguing as the title (and her passionate conversation about jazz as a progressive free form of art) sounded, I was surprised that I had no idea what jazz in the Maghreb was, let alone what it sounded like. So, I decided, I too should know a little more about this niche genre, which required some digging that led me to an afternoon listening session in a small café in Carthage.

The archaeological town is known for its 17-year-old Jazz à Carthage festival (the music event is set to make its post-pandemic comeback next April) which saw the likes of Johnny Griffin, Dhafer Youssef, and Pink Martini take to the stage in the past. And it doesn’t stop there. Tunisia is also home to another three jazz festivals, with Sicca Jazz, Tabarka Jazz, and Maghreb Jazz Days completing the list.

As I wait for my coffee, I put the opening track on play and it immediately rings a bell. It’s the indisputable jazz standard, also known as A Night in Tunisia, to which the Mediterranean country had lent its name, for reasons still unknown.

The classic melody was actually composed under the name Interlude by the great American trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie in the early forties and sung by Sarah Vaughan in different lyrics. The Tunisia tag came along later somehow. It’s rumored that the new title and lyrics were a symbol of the time African-American troops arrived on North African soil during WWII. It wasn’t until 1961, however, when it caught the attention of renowned American singer Ella Fitzgerald (often referred to as the “Queen of Jazz), that the track became the sound that we all know so well today.

But while there is no proof of Gillepsie hypothetically visiting Tunisia, another jazz legend did, only thirty years later. The Swiss composer George Gruntz, whose quick-tempo track Nemeit is featured in the playlist, partnered up with American jazz trumpeter Don Cherry and local musicians in May 1969 to put together Noon in Tunisia. Their journey in Tunisia was closely captured by German director Peter Lilienthal and the documentary is currently available on streaming platform MUBI.

The album is chock full of folkloric tunes, notably Tunisian Mezoued. You can hear the distinctive sound of zokra mixing with the quick tip-tapping of drums, the saxophone and trumpet hugging the strong beats of bendir, forming a sonic cocktail of contrasting instruments.

It’s no surprise Gruntz had chosen to couple jazz with mezoued, two rebel sounds from opposite sides of the Atlantic. While jazz’s rebellious nature finds form in its layering of rhythms and the art of improvisation, mezoued does so in bashing the status quo.

The genre stemmed from the pains and challenges faced by migrators from the rural sides of Tunisia, who were long considered as outcasts by the Baldia, a term used to describe the medina natives. In a society where social classes governed people’s musical tastes, mezoued started as a rebellious movement, ignoring the rule book of maqamat, a set of melodic modes and systems that classical genres like Malouf followed.

My coffee is here. A roasted nutty aroma fills up my corner while a psychedelic sound kicks in: Hindi Zahra’s Imik Si mik. The track is the perfect embodiment of jazz’s flirtation with Amazigh culture. The Moroccan artist’s verses in Shilha (Amazigh language native to Morocco) adds a layer of complexity to the significantly blues-y track.

Zahra’s soulful humming is then disrupted by the upbeat rhythms of Malika Zarra’s Berber Taxi, yet another testament of jazz and berber genres crossing paths, making the case for jazz as a melodic chameleon. The ease in which it unites sounds from across the North African region has given birth to various subgenres, my personal favourite being raï jazz.

This underrated sonic encounter is celebrated by artists like Karim Ziad (*plays his track Had Zmen on loop*), Algerian musician and former jazz drummer for none other than Cheb Mami and Cheb Khaled.

Another raï sound with an Algerian-Jewish and Latin musical repertoire as its backbone is Ya Maalem/Kelbi Razahi by Oran native pianist Maurice El Medioni. The perfect addition to your Rumba backyard party playlist, the track is part of his 1996 album Café Oran which features jazz figures like American clarinetist David Krakauer and trumpeter Frank London.

While I sip on my tepid cup of coffee (my OCD-self taking quicker gulps before the coffee turns cold), the playlist’s shuffle chimes in a familiar sound: Sidi Marzoug by Tunisian group Dendri Stambeli Movement.

Upon listening, I can’t shake away the echoing relationship I felt between Tunisia’s stambeli and soul jazz. The ritualistic chants of the musical troupes mirror the calling and cries of gospel choirs. A spiritual trance-like signature that is also deeply associated with Morocco’s gnawa, a genre that has formed its own subgenre with jazz, celebrated annually in the city of Essaouira at the Gnaoua World Music Festival.

More than merely a fusion or crossover genre, Maghrebi jazz is an established musical platform that bridges the sonically traditional and the audaciously experimental. What is common to both lies certainly in the beauty of a perfectly balanced marriage of sounds that urges you to just sit and listen.

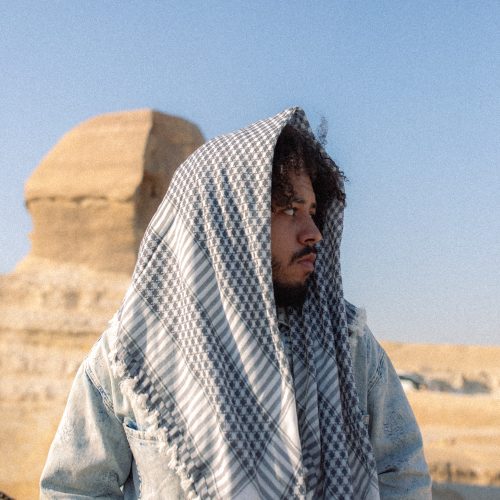

Main image: Instagram.com/@dendri_stambeli_movement