Poetry holds a strong position across the Arab world as it is considered to be one of the highest forms of literature that dates back to the 6th century— even before Islam came to be a religion. The intricate art form serves as an eloquent and powerful device for storytelling, telling tales of love, heritage, culture, and tradition. Most potently, verse is used as a means to call for liberation and justice. Palestine is home to many prominent figures in the literary scene, such as Ghassan Kafani, a revolutionary writer and leading member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), who inspired the generations that came after him.

An admirable art mastered by a few has often placed the country’s ongoing plight under a 75-year violent military occupation in metaphors that speak of liberation and resilience. The words of these writers continue to live on, and echo in their significance despite the attempts by the apartheid state to silence them. Over the decades, Palestinian poets have risked arrest, exile, and even death in the name of their prose. But still, their expression remains unchanged and an integral part of social movements across the region, speaking the minds and hearts of many, and voicing the never-ending unfathomable injustices that the region faces.

Below, a list of 7 revolutionary Palestinian poets who made a significant impact with their words.

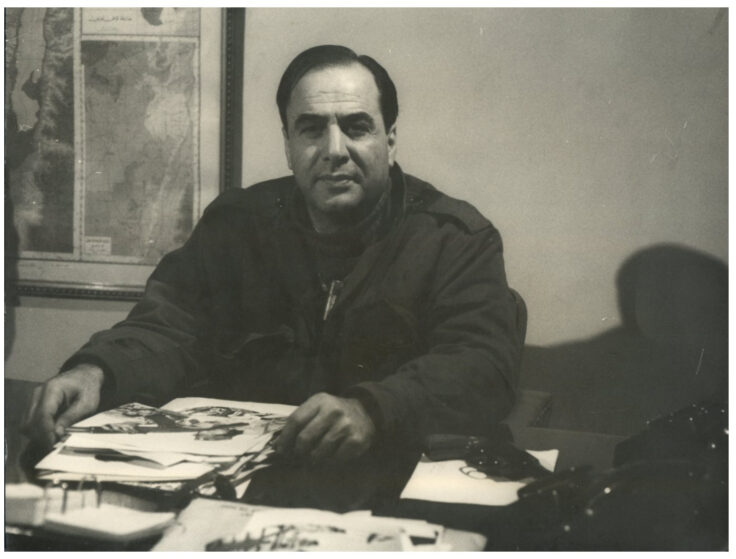

Mahmoud Darwish

Mahmoud Darwish is almost the eponym of the entire Palestinian struggle. The author of 30 books of poetry, in which he puts his heart and soul into his books, the writer beautifully transformed his pain over the dispossession of his homeland into beautiful poetry. An unwavering symbol of Palestinian resistance, he was among the few poets who expressed in the most searing and stark ways the realities and injustice of dispossession, rootlessness of refugees, and the ache of belonging to one’s land in the face of adversity. His poetic prowess stands as a testament to the power of the written word.

His book, Journal of an Ordinary Grief (2010) is dedicated to the people of Gaza. In it, there is a section entitled Silence for the Sake of Gaza.

Gaza is not the most beautiful of cities.

Her coast is not bluer than those of other Arab cities.

Her oranges are not the best in the Mediterranean.

Gaza is not the richest of cities.

And Gaza is not the most polished of cities, or the largest. But she is equivalent to the history of a nation, because she is the most repulsive among us in the eyes of the enemy – the poorest, the most desperate, and the most ferocious. Because she is a nightmare. Because she is oranges that explode, children without a childhood, aged men without an old age, and women without desire. Because she is all that, she is the most beautiful among us, the purest, the richest, and most worthy of love.

…

Gaza is far from its relatives and close to its enemies, because whenever Gaza explodes, it becomes an island and it never stops exploding. It scratched the enemy’s face, broke his dreams and stopped his satisfaction with time.

Because in Gaza time is something different.

Because in Gaza time is not a neutral element.

It does not compel people to cool contemplation, but rather to explosion and a collision with reality.

Time there does not take children from childhood to old age, but rather makes them men in their first confrontation with the enemy.

Time in Gaza is not relaxation, but storming the burning noon. Because in Gaza values are different, different, different.

The only value for the occupied is the extent of his resistance to occupation. That is the only competition there. Gaza has been addicted to knowing this cruel, noble value. It did not learn it from books, hasty school seminars, loud propaganda megaphones, or songs. It learned it through experience alone and through work that is not done for advertisement and image.

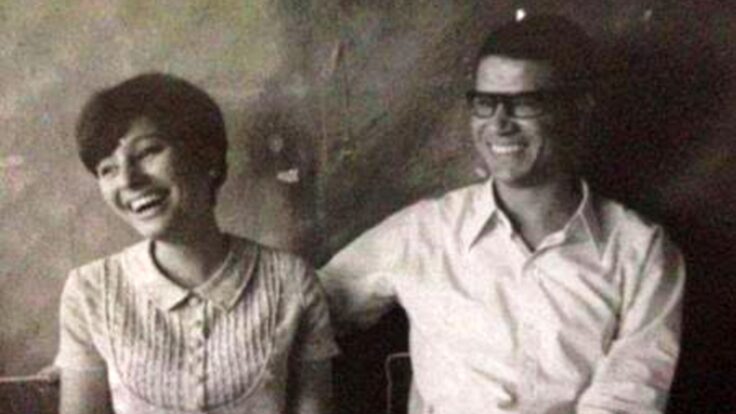

Tamim al-Barghouti

Known widely in the Arab world as “the poet of Jerusalem,” Tamim al-Barghouti is also a columnist, political scientist, and cultural commentator. The Egyptian-Palestinian was born in Cairo in 1977 to a literary family. His father was the Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti and his mother was the renowned Egyptian novelist Radwa Ashour. During peace talks with Israel in the late 1970s, the writer’s father was one of the Palestinian intellectuals forced out of Egypt by then-president Anwar Sadat. It was both sides of his heritage that influenced the younger Barghouti’s poetry and writing, which was highly critical of both the Egyptian government and the Israeli occupation.

As he paints a portrait of what life is like for Palestinians living with checkpoints and harassment from settlers in his poem, In Jerusalem, Barghouti discusses the Israeli occupation of his homeland.

In Jerusalem, there are walls of basil

In Jerusalem, there are barricades of concrete

In Jerusalem, the soldiers marched with heavy boots over the clouds

In Jerusalem, we were forced to pray on the asphalt

In Jerusalem, everyone is there but you.

And History turned to me and smiled: “Have you really thought that you would overlook them and see others?

Here they are in front of you;

They are the text while you are the footnote and margin O son, have you thought that your visit would remove, from the city’s face,

the thick veil of her present, so that you may see what you desire?

In Jerusalem, everyone is there but you.

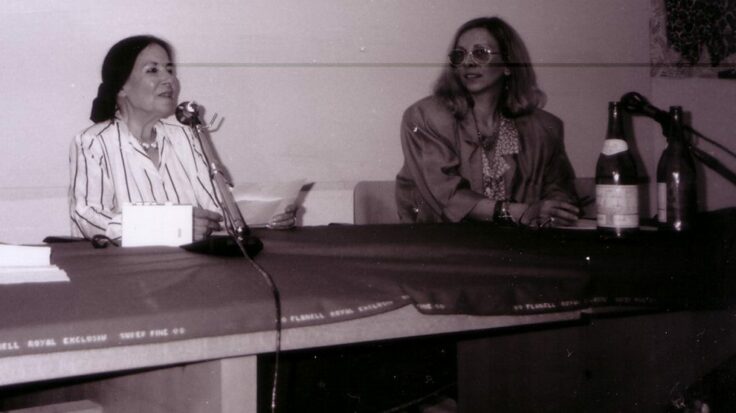

Fadwa Tuqan

Born in Nablus, Fadwa Tuqan’s prose spoke of resistance, whilst empowering marginalized voices. Her introduction to poetry was made through her brother who is no other than the illustrious Ibrahim Tuqan, another Palestinian nationalist poet whose work is believed to have rallied Arabs during their revolt against the British mandate. In her writing, the poet tackled sentiments surrounding displacement that came with being expelled from your homeland, and the dream of returning to that homeland. Tuqan’s poetry was often informed by the colonial Balfour Declaration which was announced in 1917, where the British government promised the Jewish people a homeland in Palestine despite its indigenous population. Another big focus of Tuqan’s poems was the Nakba (Catastrophe), which resulted in the displacement of more than 700,000 Palestinians to make way for the state of Israel in 1948. She was notable for highlighting the injustices inflicted on her people while celebrating their spirit of resistance, which can be seen in her poem Ever Alive.

My beloved homeland

No matter how long the millstone

Of pain and agony churns you In the wilderness of tyranny, They will never be able

To pluck your eyes

Or kill your hopes and dreams Or crucify your will to rise

Or steel the smiles of our children Or destroy and burn,

Because out from our deep sorrows,

Out from the freshness of our spilled blood Out from the quiverings of life and death Life will be reborn in you again………

Kamal Nasser

Born in Gaza, Kamal Nasser was a fervent political activist who penned his impassioned words in the name of Arab unity and against the oppressive Israeli occupation of Palestine. His unwavering commitment to shedding light on the 1948–49 forced displacement of nearly 700,000 Palestinians from their homeland by invading Zionist forces made him a prime target for Israeli authorities. In 1967, Kamal was forcefully deported from Palestine, an event that only fueled his determination. Rather than succumbing to exile, Kamal found renewed purpose in his struggle. He became a vital member of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1968, earning a place on its Executive Committee in 1969. Over the course of four years, from 1969 to 1973, Kamal directed the PLO’s media and information initiatives, tirelessly working to amplify awareness of the Palestinian cause. Kamal was not only a passionate activist but also a prolific author, producing both prose and poetry that centered on the themes of Arab unity and the Palestinian yearning for independence. His words resonated with those who shared his vision of liberation and justice. However, Kamal’s life was tragically cut short. In 1973, he fell victim to an assassination carried out by undercover Israeli commandos during a raid on his home in Beirut, a testament to the profound impact of his words and activism on the struggle for Palestinian rights and self-determination. A number of his poems have been translated into English, including The Story.

I will tell you a story

A story that lived in the dreams of people

A story that comes out of the world of tents

Was made by hunger, and decorated by the dark nights

In my country, and my country is a handful of refugees

Every twenty of them have a pound of flour

And promises of relief, gifts and parcels

It is the story of the suffering group

Who stood for ten years in hunger

In tears and agony

In hardship and yearning

It is a story of a people who were misled

Who were thrown into the mazes of years

But they defied and stood

Disrobed and united

And went to light, from the tents,

The revolution of return in the world of darkness

Hala Alyan

A Palestinian-American writer, poet, and clinical psychologist who specializes in trauma, addiction, and cross-cultural behavior, through her words, Hala Alyan delves into the intricate facets of identity, plumbing the depths of displacement, especially within the vast tapestry of the Palestinian diaspora. Her novel Salt Houses has earned global recognition, including the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, the Arab American Book Award, and the Chautauqua Prize. In the realm of poetry, her award-winning collections, including The Twenty-Ninth Year, reveal an intimate command of language and a unique ability to capture the essence of Palestinian identity.

I had lived in a desert before. I did. I forgot the za’atar my mother said she fed me in Iraq. I forgot my grandmother’s house in Soo-ree-yaa. There I was, eating the prickly pears even though they always made my tongue itch. A teacher in Texas told me I’d never learn how to pronounce my own name in English and she was right. I wept until my mother took me to McDonald’s. In that house I was the only child. I danced in the hot winter. In ten years, a boy will leave marks on my arm because I call him a redneck. I stole a Barbie pink windbreaker from the cubbyhole at school. There was nothing in the pockets. Even before the sun rose, my father went outside to smoke and watch the birds fly east. He loved the ugly ones best of all.

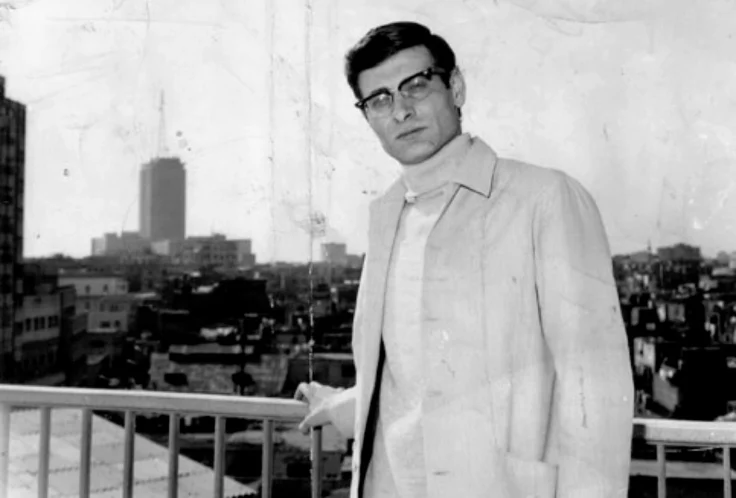

Mourid Barghouti

The I Saw Ramallah writer, Mourid Barghouti can be referred to as a poet in exile and a champion of the Palestinian cause. Barghouti was born in the Palestinian village of Deir Ghassaneh on the outskirts of the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah, four years before the Nakba. He moved to Egypt in 1963 to pursue a degree in English literature at Cairo University, and was not able to return to Ramallah for another 30 years. In 1977, he was exiled from Egypt after he vehemently opposed the Oslo Accords and the outcome of the agreements. He lived in several countries within the region including Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq.

I Saw Ramallah is a memoir of exile and displacement and was inspired by his return to Ramallah following the signing of the Oslo Accords in the 1990’ s. Edward Said referred to the work as “one of the finest existential accounts of Palestinian displacement.”The book won him the Naguib Mahfouz Prize in Literature in 2017.

The Occupied Territories; you think there is absolutely no way you can get to it. Do you see how close it is? How touchable? How real?

When the eye sees it, it has all the clarity of earth and pebbles and hills and rocks. It has its colors and its temperatures and its wild plants too.

Who would dare to make it into an abstraction now that it has declared its physical self to the senses?

It is no longer ’the beloved’ in the poetry of resistance, or an item on a political party program, and it is not an argument or a metaphor. It stretches before me, as touchable as a scorpion, a bird, a well; visible as a field of chalk, as the prints of shoes.

I asked myself, what is so special about it except that we have lost it? It is a land, like any land.

We sing for it only so that we may remember the humiliation of having had it taken from us. Our song is not for some sacred thing of the past but for our current self-respect that is violated anew every day by the Occupation.

Remi Kanazi

Using his prose to bring attention to the ongoing systems of oppression in the Occupied Territories, the Palestinian-American poet, writer, and activist Remi Kanazi speaks of the Nakba, cultural boycotts, US militarism abroad, mass incarceration, and a plethora of injustices that occur around the world in his works. Kanazi not only aims to educate people through his words, but to encourage them to contribute in changing the status quo— to do something. In A Poem for Gaza, Kanazi painfully captures the suffering of his people.

I never knew death until I saw the bombing of a refugee camp

Craters filled with disfigured ankles and splattered torsos

But no sign of a face, the only impression a fading scream

I never understood pain

Until a seven-year-old girl clutched my hand

Stared up at me with soft brown eyes, waiting for answers

But I didn’t have any

I had muted breath and dry pens in my back pocket

That couldn’t fill pages of understanding or resolution

In her other hand she held the key to her grandmother’s house

But I couldn’t unlock the cell that caged her older brothers

They said, we slingshot dreams so the other side will feel our father’s presence

A craftsman

Built homes in areas where no one was building

And when he fell, he was silent

A .50 caliber bullet tore through his neck shredding his vocal cords

Too close to the wall His hammer must have been a weapon

He must have been a weapon

Encroaching on settlement hills and demographics

So his daughter studies mathematics

Seven explosions times eight bodies

Equals four Congressional resolutions

Seven Apache helicopters times eight Palestinian villages

Equals silence and a second Nakba

Our birthrate minus their birthrate

Equals one sea and 400 villages re-erected

One state plus two peoples…and she can’t stop crying

Never knew revolution or the proper equation

Tears at the paper with her fingertips

Searching for answers

But only has teachers

Looks up to the sky and see stars of David demolishing squalor with hellfire missiles

She thinks back words and memories of his last hug before he turned and fell

Now she pumps dirty water from wells, while settlements divide and conquer

And her father’s killer sits beachfront with European vernacular

She thinks back words, while they think backwards

Of obscene notions and indigenous confusion

This our land!, she said

She’s seven years old

This our land!, she said

And she doesn’t need a history book or a schoolroom teacher

She has these walls, this sky, her refugee camp

She doesn’t know the proper equation

But she sees my dry pens

No longer waiting for my answers

Just holding her grandmother’s key…searching for ink