Today marks more than 900 days since Afghan girls were first banned from school. After two years of Taliban rule, Afghan women and girls continue to bear the brunt of the suffering, with nearly 80% of those in need being women and children. Relentless restrictions imposed on women in society exacerbate the economic crisis, forcing mothers to send their children to work to earn money for food, resulting in a sharp increase in child labor. Restrictions on women’s access to work also contribute to the failing economy, causing an estimated economic loss of up to $1 billion, equivalent to about 5% of Afghanistan’s GDP.

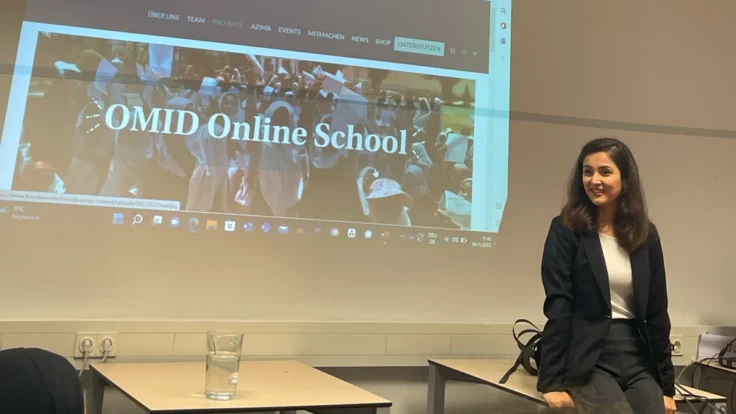

As bleak as the reality is, stories of unparalleled courage and unwavering determination emerge as a balm in the face of a cruel and ruthless world that determines which struggles are to be put on the agenda. Highlighting these stories is crucial to propel women to continue on the hassle-filled road to complete emancipation. This is why, when the story of Omid, the online school allowing girls to get a proper education, popped up on my LinkedIn feed, I couldn’t help but contact Zahra Hashimi, the founder, to discuss her bold and courageous endeavor and learn more about the challenges faced by Afghan girls.

Humbly preferring to be introduced as a human being without adding any other labels, Hashimi is an Afghan human rights activist based in Vienna, Austria. She is known for her work with the Omid Online School, which she founded to address the education ban for Afghan girls. Additionally, Hashimi works as a community manager and content creator for Fremde Werden Freunde (Strangers Become Friends), an organization that promotes the social inclusion of migrants in Austrian society. She is also a journalist and podcaster for Persian and Austrian media. Her diverse roles reflect her commitment to social activism, education, and media engagement.

Her educational initiative hardly comes as a surprise to those who know the human right activist and her personal journey. Growing up in Iran, she began her education at the age of six, attending a concealed school for immigrants, where she learned basic reading and math.

Shortly after, her family relocated back to Afghanistan after the Taliban was overthrown in 2001. Even though she witnessed a post-Taliban era, real life was not that easy for her and her peers as she recalls, “The hijab was mandatory and the threat of explosions still persisted. I remember hearing some explosions when I was a kid. But, despite the dangers and restrictions, there was a breeze of freedom; Afghans would not renounce easily.”

Driven by a strong desire for education, the then 16-year-old succeeded in persuading her father to allow her to pursue college— something that was not that common for a girl to do without relentless negotiation and persuasion. After obtaining her post-secondary education, Hashimi began working in an education center for different levels.

Today, her background as a girl whose right to education was not taken for granted, enhanced by being a former teacher, makes her very concerned about the future of Afghan girls and she is determined to come up with any solution that can alleviate their plight.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Omid online school | مکتب آنلاین امید (@omid_online_school)

So, in March 2022, she decided to offer teaching on her private Instagram account that offered basic courses aimed at young girls. To her surprise, more than 300 students were registered in only 20 days. University students who were forced to renounce their education offered to teach classes in Farsi and follow the Afghan curriculum, so the students would be able to resume their education once the “gender apartheid” is lifted. In a country where women were aggregated upon and banned from any public life, female solidarity emerged as a driving force to mitigate the impact of such abhorrent laws and decrees.

The first thing Hashimi told me before introducing herself was, “I don’t know if people in the Middle East use the same word for ‘hope’ but in Afghanistan we say ‘omid.’ We want to give these girls hope in a better future. And Omid, the school, is hanging on to the faith that one day it will shutter its doors as schools reopen to girls to get the education they deserve and pursue the dreams that every kid nurtures about a bright future.”

Read on to learn more about Omid and the challenges it has to face just to alleviate the plight of Afghan children.

What prompted you to take this leap of faith to launch an online school and defy the Taliban rules?

I was deeply disturbed by the news of the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan in August 2021 and the resulting ban on girl’s right to education beyond the age of 11. My first reaction revolved around advocacy and protest. I took part in all the demonstrations in Vienna and made my way to the Austrian parliament to speak up about the plight of women in this very bleak period. But, the more I spoke, the more I felt unheard and invisible. I felt disillusioned that no one was able to help or make tangible change. This is when I decided to take action and channel my energy to create something for Afghan children deprived of education crying in front of their schools’ closed doors. As a teacher myself, I saw an opportunity to make a difference and came up with the idea of teaching some of the kids. I posted on Instagram, offering to teach 50 students basic subjects and provide internet access.

Within days, my offer received an overwhelming response, with over 300 registrations. University students, who were also banned from pursuing their education, and female teachers started to contact me and propose their help. Things evolved to a more structured approach, and in less than 20 days, we launched classes with 300 students. The school grew rapidly, with 113 students by the end of the first year and over 1300 registrations by April 2023.

What does Omid offer the students?

At Omid, we are committed to offering a comprehensive education that aligns with the Afghan Ministry of Education’s (MoE) curriculum, including all the regular subjects– that are math, Dari, biology, Pashto, chemistry, physics, English, history, geography, and Islam–– and some extracurricular subjects taught in seminar format twice a month. Initially, we aimed to provide continuity by following the MoE curriculum, anticipating the eventual reopening of traditional schools in Afghanistan. However, as restrictions on women’s freedoms intensified, we adapted our approach to ensure continued access to education for our students.

As the girls are always home, the school has developed to be the only activity they can do and keep themselves busy with. Despite financial constraints, we strive to enrich the learning experience through workshops, competitions, and holiday programs, fostering a vibrant educational community. This comes from the urgent need of our students to do something during the holidays. Our workshops cover various topics, including article writing, with winners recognized for their achievements. We see active participation, with 50 to 70 students attending these events regularly.

The school is now a sanctuary in the midst of the gender apartheid enforced by the Taliban and the deteriorating mental health among Afghan women. Were you able to find a way to support your students navigating these harsh circumstances?

Mental health support is essential, especially in this case. No one can depict a little girl confined home unable to go out or decide what to do. They are facing various serious challenges, including familial opposition to education, forced marriages, threats from societal and political forces, and harassment due to their pursuit of education, among others. They feel isolated and desperate, unable to foresee any agency in their future. This is why we strive to provide a safe space for students to express themselves and seek assistance through private counseling and referrals to Persian therapists. It’s worth mentioning that finding Persian female therapists to assist us with this mission is quite hard. So, we worked on addressing the emotional needs of our students internally by ensuring access to confidential counseling sessions.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Omid online school | مکتب آنلاین امید (@omid_online_school)

As easy as the solution of online learning may seem to some people, what are the main challenges hindering Omid’s impact?

Omid faces several multifaceted challenges, primarily revolving around funding and official recognition. Despite providing hope and education to hundreds of Afghan children, we struggle to secure financial support to sustain our operations. The lack of donors and donations is impeding our growth and threatening our continuity. While some other schools charge fees, we refuse to do so, as many families in Afghanistan cannot afford it. This financial constraint limits the number of students we can accommodate and teachers we can hire, preventing us from expanding our reach.

The lack of support from larger organizations and governments, who prioritize bureaucratic processes over urgent humanitarian needs, shows that other sustainable funding models need to be found to empower local initiatives. The school’s unofficial status is also a significant obstacle as girls wouldn’t be able to get official certification upon graduation. We are negotiating with the government to get these accreditations, but I am not optimistic about this. Another significant challenge is providing devices and internet access, as many students and teachers in Afghanistan lack the resources to get a phone or laptop and find reliable connectivity. With the donations we get, we are only able to provide internet for teachers, who are risking their safety and financial stability to be part of the school.

People usually forget that the ban includes female teachers who are also prohibited from carrying out their work and forced to be back home with no access to public life. Can you tell us more about the teachers of Omid?

Teachers are not allowed to provide education for girls. Under Taliban rule, female teachers are hunted and clandestine initiatives are prosecuted. These dedicated women found themselves with no job nor financial resources, but some of them are sacrificing their physical and financial security to ensure that students have access to quality education at schools like Omid. Despite financial hardships, many teachers continue to volunteer, prioritizing education over their own financial security. Their dedication is inspiring and highlights the critical role of education in our community.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Omid online school | مکتب آنلاین امید (@omid_online_school)

Still, it’s not evident for people to keep volunteering, no matter how steadfast and committed the person is, in these complicated circumstances and in the midst of a flagrant economic crisis. So the constant turnover of volunteer teachers due to financial constraints poses a significant challenge. I am grateful to all the teachers that have been part of Omid. And, I am doing my best to guarantee stable funding for sustaining our operations and retaining qualified teachers. Therefore, securing stable funding is paramount to retaining these qualified teachers and ensuring consistent educational opportunities for our students, ultimately shaping a brighter future for marginalized communities in Afghanistan.

As reports from human rights organizations about the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan show alarming data about poverty rates and the decline of health, education, and livelihood services, how is this impacting Omid?

Poverty is a significant barrier to education in Afghanistan. The financial constraints faced by families prevent them from affording devices for their children or covering internet expenses, which are relatively high in Afghanistan compared to the average income. This leads to a high dropout rate and a decrease in the number of students actively engaged in learning.

Even if phones and internet access are available, we usually get siblings from different grades using one device and unable to follow and participate in their online classes consistently. But, we try our best to give them tips on how to use their internet time equally and proactively do their homework. We had two sisters who had no knowledge of how to use a mobile phone. Through perseverance and support, they became top performers in their classes. Our girls are doing their best with the little they have to get education and learn.

How do you ensure the safety and privacy of teachers and students in such a volatile environment?

We prioritize the safety and privacy of our teachers and students by implementing strict protocols. Teachers are instructed not to share any private information such as last names, personal photos, or details about their personal lives. They are required to wear masks during online classes and refrain from using social media platforms to maintain anonymity. Similarly, students are encouraged not to share any personal information that could compromise their safety. Additionally, we have enforced a policy against posting photos, using full names, or sharing any identifying information that could pose a threat to individuals’ safety. Unfortunately, some of our students and teachers have faced threats and intimidation from the Taliban. But, our community remains resilient and committed to pursuing education in a safe environment.

Carrying this mission despite all of these challenges is quite inspiring for us, but how do you really feel about it?

Indeed, sometimes I contemplate the magnitude of our mission in the face of such immense challenges. Teaching only a few hundred children in Afghanistan may seem insignificant when compared to the millions in need. However, I keep pushing myself to believe that even if I can change one life, my efforts are worthwhile. Whenever I feel desperate, I reflect on my own journey and find solace in it. I was the first in my family to attend university, I faced opposition but persisted, inspiring other family members and relatives to follow suit. This experience taught me that even one person’s courage can ignite change and shape the destiny of future generations. Thus, while I may question the broader impact of my actions, I recognize the importance of each individual’s journey and the ripple effect it can have on the world.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Omid online school | مکتب آنلاین امید (@omid_online_school)

I am really disappointed by the lack of support from larger organizations and governments and believe that the world has given up on Afghan women. The injustices, such as the unjust arrest of Hazara girls, often go unnoticed by the international community. This makes me skeptical if the world really cares about our miserable situation and also more determined to do my part to help my people. Despite these obstacles, my team and I remain steadfast in our commitment to providing education and hope to Afghan children.