Lebanon became known as ‘the Paris of the Middle East’ during the 1950s and 60s – but despite it’s buzzy international reputation, very few photographs of the country’s golden era have resurfaced.

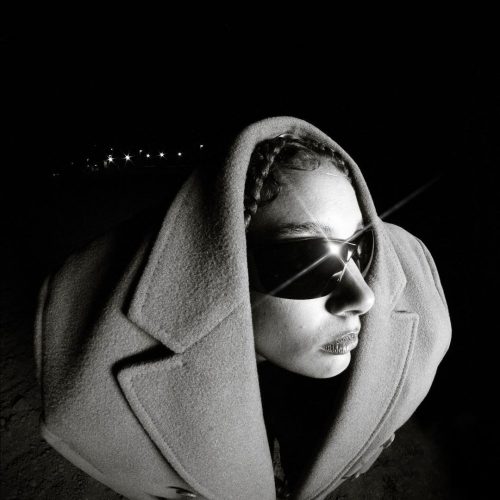

For 50 years, acclaimed photographer Hashem El Madani captured (by his own estimate) 90 per cent of the city of Sayda’s population, amassing more than 75,000 images, capturing the everyday lives of Lebanese people like never before.

And thanks to the Arab Image Foundation, a gargantuan archive of his work has been unearthed from the dusty boxes that had sat for decades in his studio, which became known as Sherhrazade,named after the storyteller from One Thousand and One Nights.

Since 2016, the non-profit organization, which works to preserve photographs from the region, launched a digitalization project, which aims to bring Hashem Al Madani’s portraits along with their extensive photography collection, which dates back over 150 years, to the internet with an encyclopedic online.

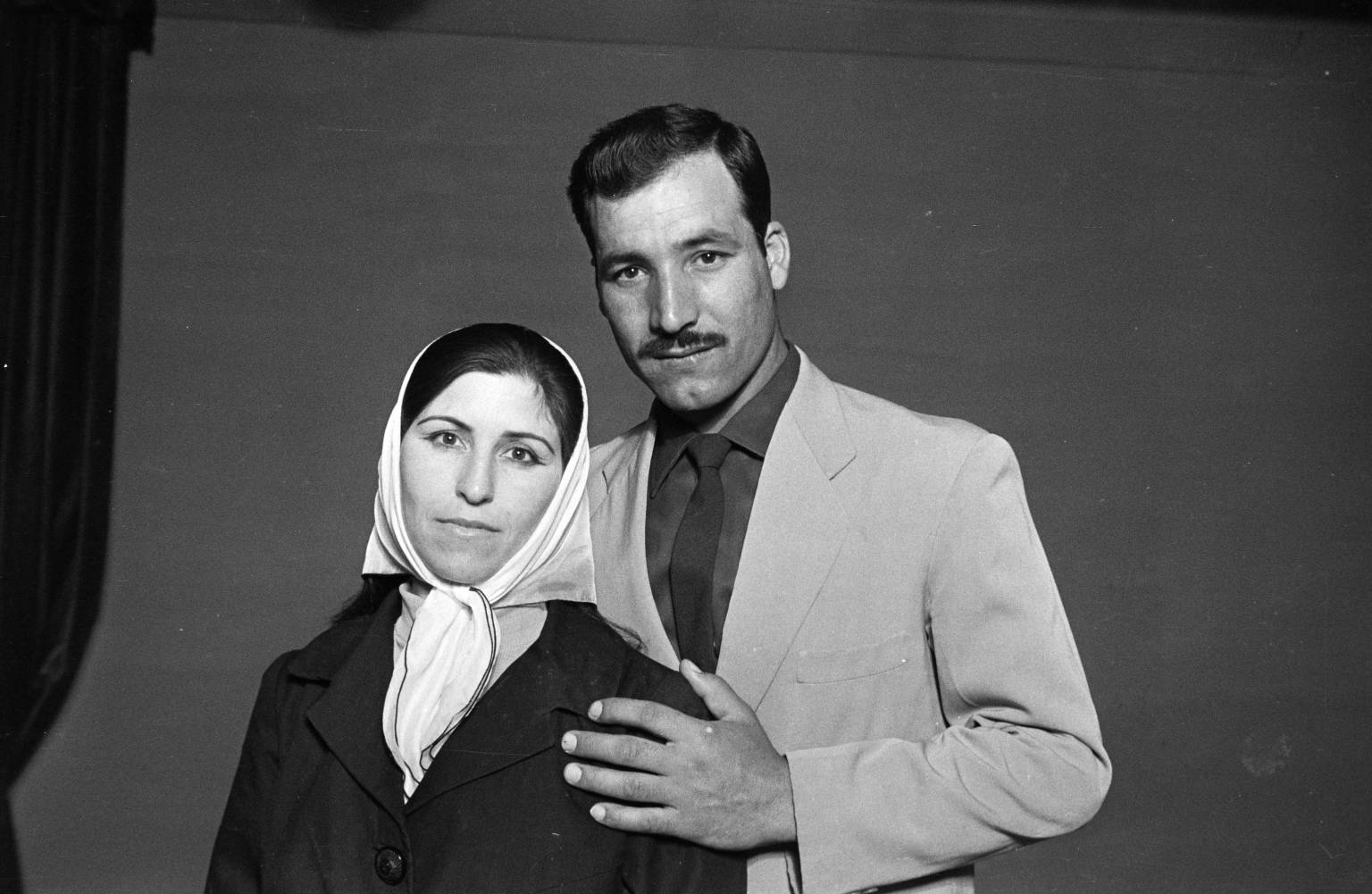

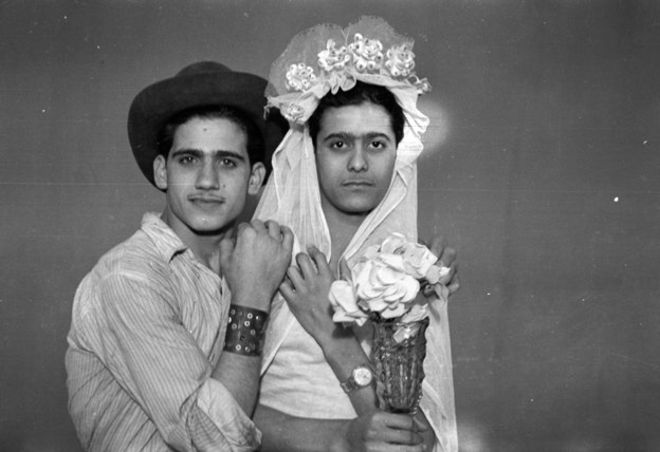

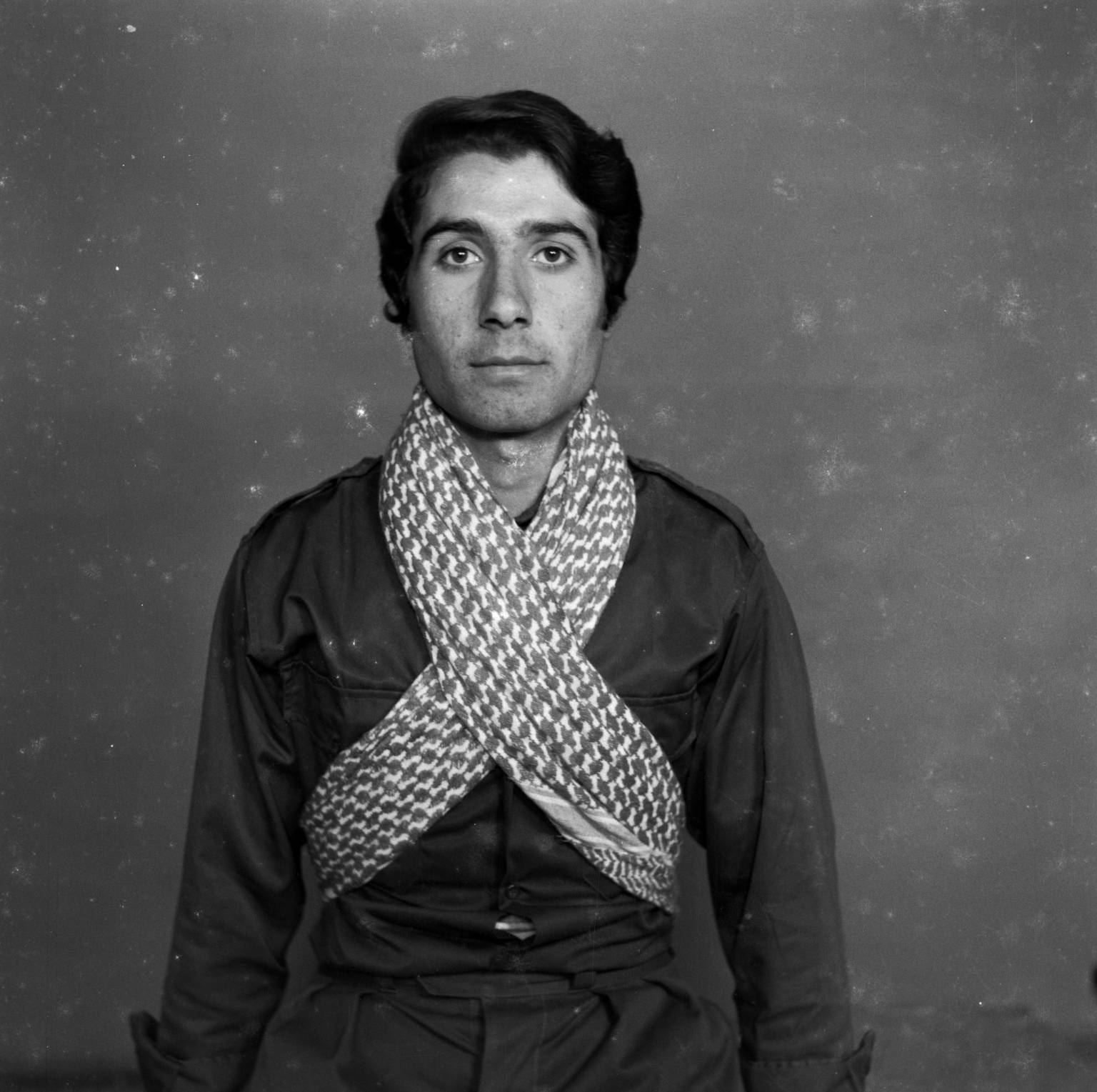

El Madani’s work has been compared to the renowned portraiture artist August Sanders, the German photographer behind one of the world’s greatest portrait collections. El Madani’s sitters ranged from soldiers proudly carrying their guns to unassuming men and women kissing each other on the cheek. Anyone who wanted to be photographed was welcomed in to his studio, where they would pose in front his simple backdrops.

He allowed his subjects to decide how they’d like to be represented. Some men wrested, others smiled and posed next to El Madani’s blond-haired, blue-eyed life-size cut-out model. Many took off their clothes and showed off their muscles, couples kissed, and some chose to remain serious, gazing directly at his camera.

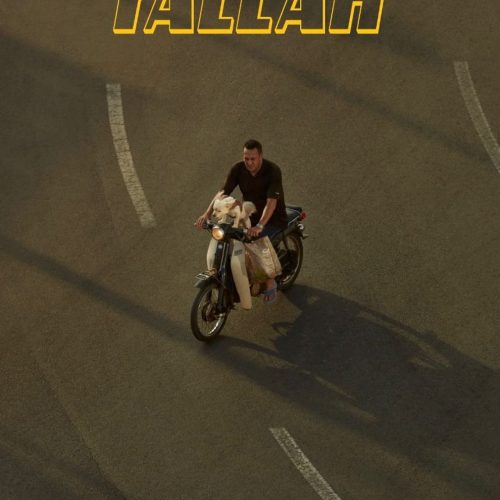

His studio reached its climax in the 60s and 70s, until business slowed down in 1982 following the Israeli Invasion. Over the years that followed, his photos had gone practically unnoticed until 1999, when the Arab Image Foundation’s Akram Zaatari, who works to preserve photography from the region, began searching for photographs of vehicles in the region. El Madani’s archive included a few, but it was the portraits tucked away in dusty boxes that captured Zaatari’s attention.

Since then, his work went on display across the world in institutions like the Tate Modern and London’s National Portrait gallery. And with the Arab Image Foundation’s soon-to-be-launched online library, the late artist’s work is bound to live on forever.